- Project two

- #2

- May 2019

Challenges and opportunities to improve

What’s been learned about mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain

Introduction

Mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain are significant issues affecting the health of the UK population. The Q Lab and Mind have been working together, collaborating with others across the UK, to explore the experiences of people living with both conditions, to understand how care can be designed to better meet their needs.

The worse your physical pain is, the worse your mental health is. I don’t think there’s any question about that, the two go together. Does it matter which comes first? From where I’m sitting, pain is pain. [But because] I have a very long history of mental health problems, I present with a pain problem and the first thing my GP says to me is, “Yes, well you’re very anxious.” I’m like, “Yes, but I’m also in pain.” “Yes, but you’re very anxious.”

Lab participant

2019

This essay brings together insights generated from a number of collaborative research activities to give an overview of why this is a challenge that warrants attention, and highlights promising opportunities to improve care. The relationship between mental health and persistent back and neck pain is complicated as it affects people differently. This essay explores the implications of these differences, to enable us to understand how this informs what support and services are needed to improve the health and care of people living with both conditions.

Evidence tells us that the current health and care system is not meeting the needs of people living with both mental and physical health conditions. Although this essay focuses specifically on the relationship between mental health and persistent back and neck pain, as the Mental health and persistent pain: an introduction essay outlines, this learning connects to wider efforts to give greater parity of esteem between mental and physical health and emphasises the importance of the relationship between the two.

This essay is split into five sections:

Who this essay is aimed at?

For people with experience and expertise in mental health and/or persistent back and neck pain, we hope this essay will resonate, be a useful resource to share with others and make the case for change. For people who are less familiar with the topic, this essay gives a rounded overview, with insights and evidence that inspire ideas and action. For everyone, we hope this essay highlights the opportunities to improve care for people living with both mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain.

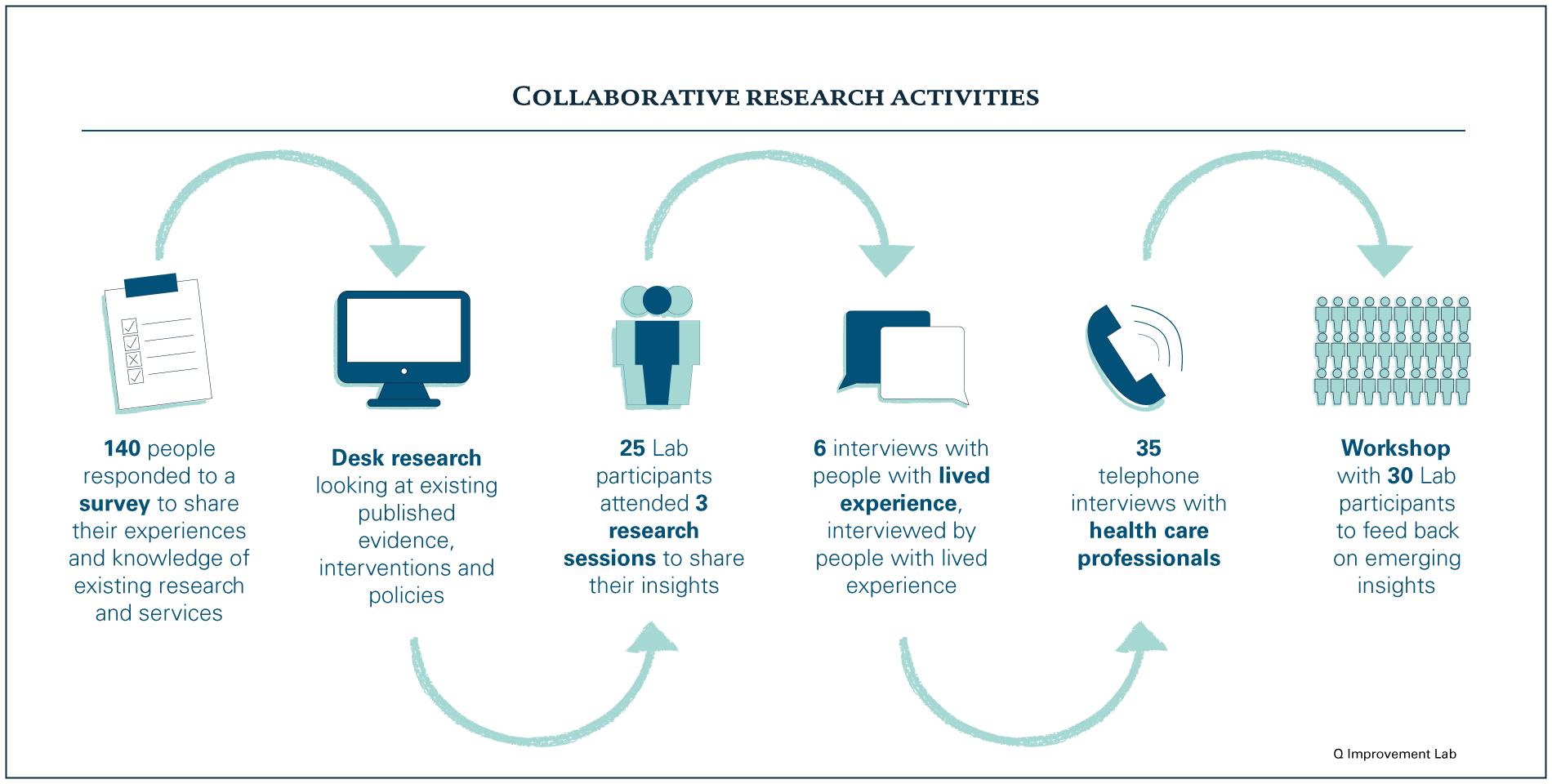

Methodology

The insights in this essay come from collaborative research activities with more than 150 people with varied experience and expertise in mental health and/or persistent back and neck pain. This includes people who volunteered to collaborate with the Q Lab and Mind on this project as Lab participants.

By working together, the aim was to surface what is known on this topic and the opportunities to improve care. We recognise that most people who contributed are based in England and Wales and have been recruited largely through the Health Foundation and Mind’s networks. This means the majority of Lab participants have either clinical expertise or have been living with the conditions for a number of years and are more confident sharing their experiences, so may not fully represent all demographic groups.

Living with both mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain

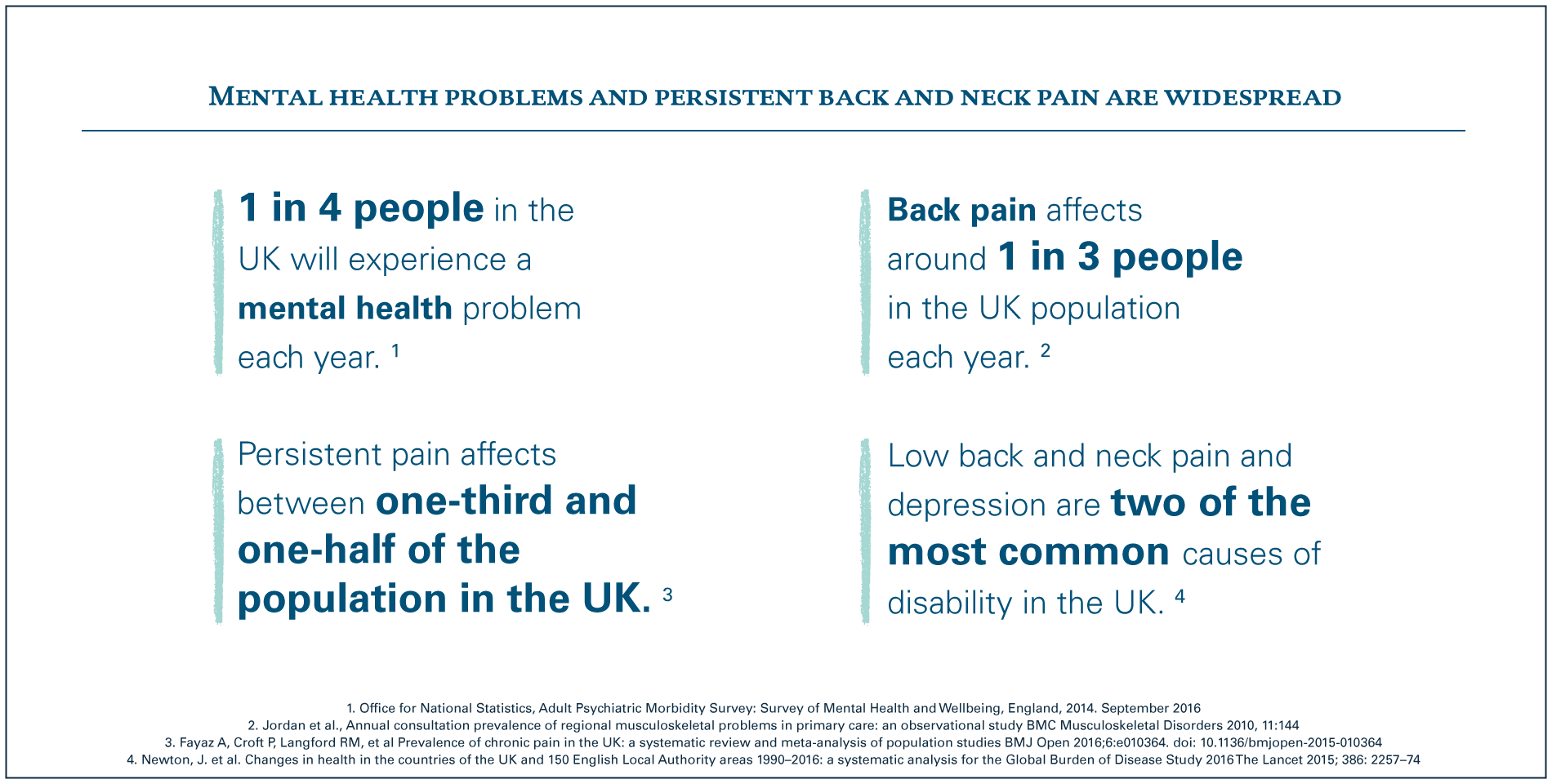

Many of us will have experienced either back and neck pain or mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety.

When we talk about mental health problems, we are referring to feelings, thoughts, reactions and emotions that prevent you from feeling well. They are a common human experience: most people will have times when they feel anxious or low. This can become a mental health problem if it impacts on your ability to live your life as fully as you want to, when the issues don’t go away after a couple of weeks, or they come back over and over.1

When we talk about mental health problems, we are referring to feelings, thoughts, reactions and emotions that prevent you from feeling well. They are a common human experience: most people will have times when they feel anxious or low. This can become a mental health problem if it impacts on your ability to live your life as fully as you want to, when the issues don’t go away after a couple of weeks, or they come back over and over.1

Persistent pain, particularly related to the back and neck, is also very common. For some people, the pain may have originated from something known, such as an accident or injury, or be linked to a long-term health condition. For others it may not have an obvious cause, and may have developed gradually, and may be associated with feeling stressed or run down.2 Usually this pain will start to get better within a few weeks. However, for some people this pain persists and is something they live with every day. This is persistent pain, which is also referred to as chronic pain.

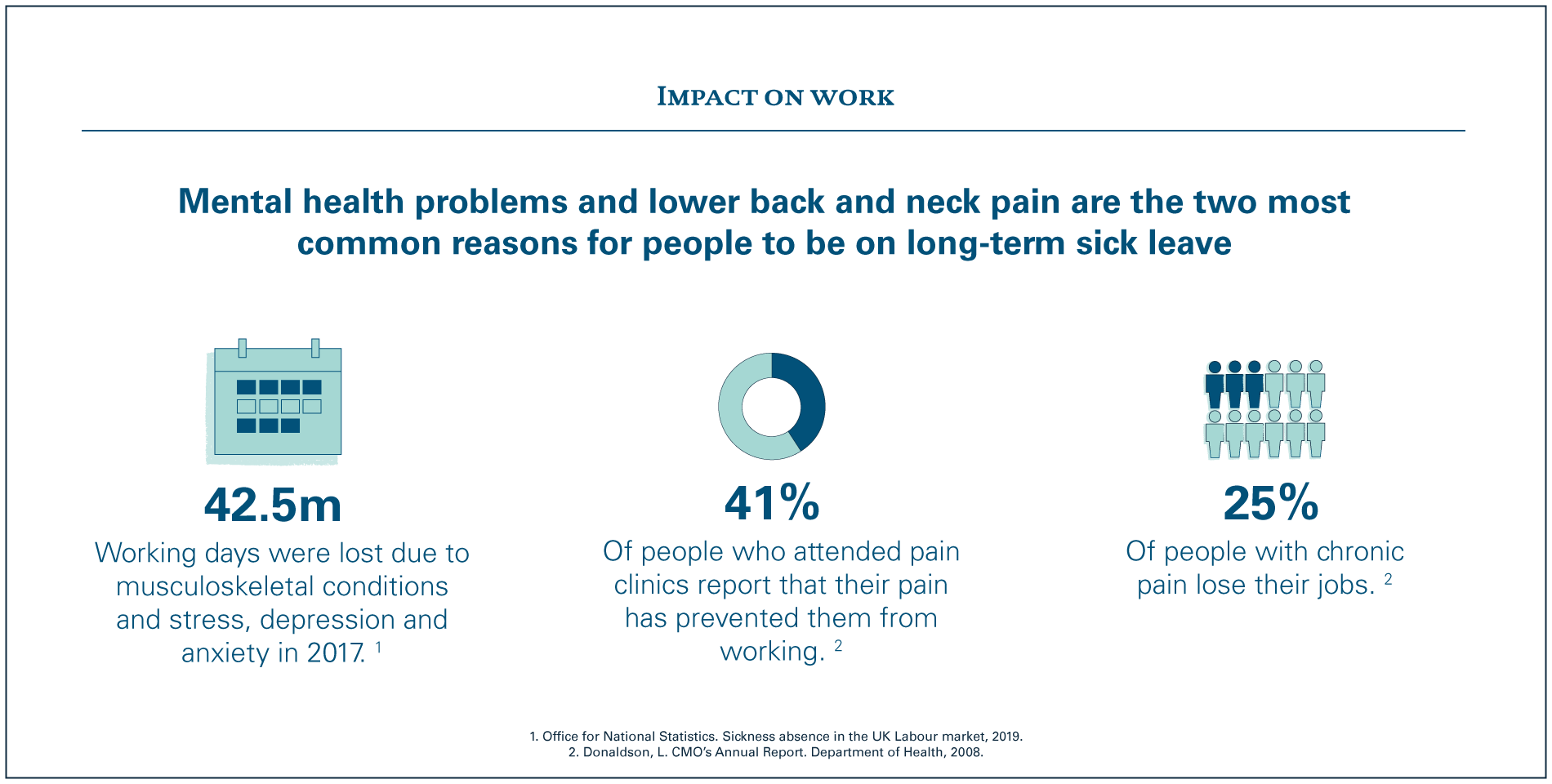

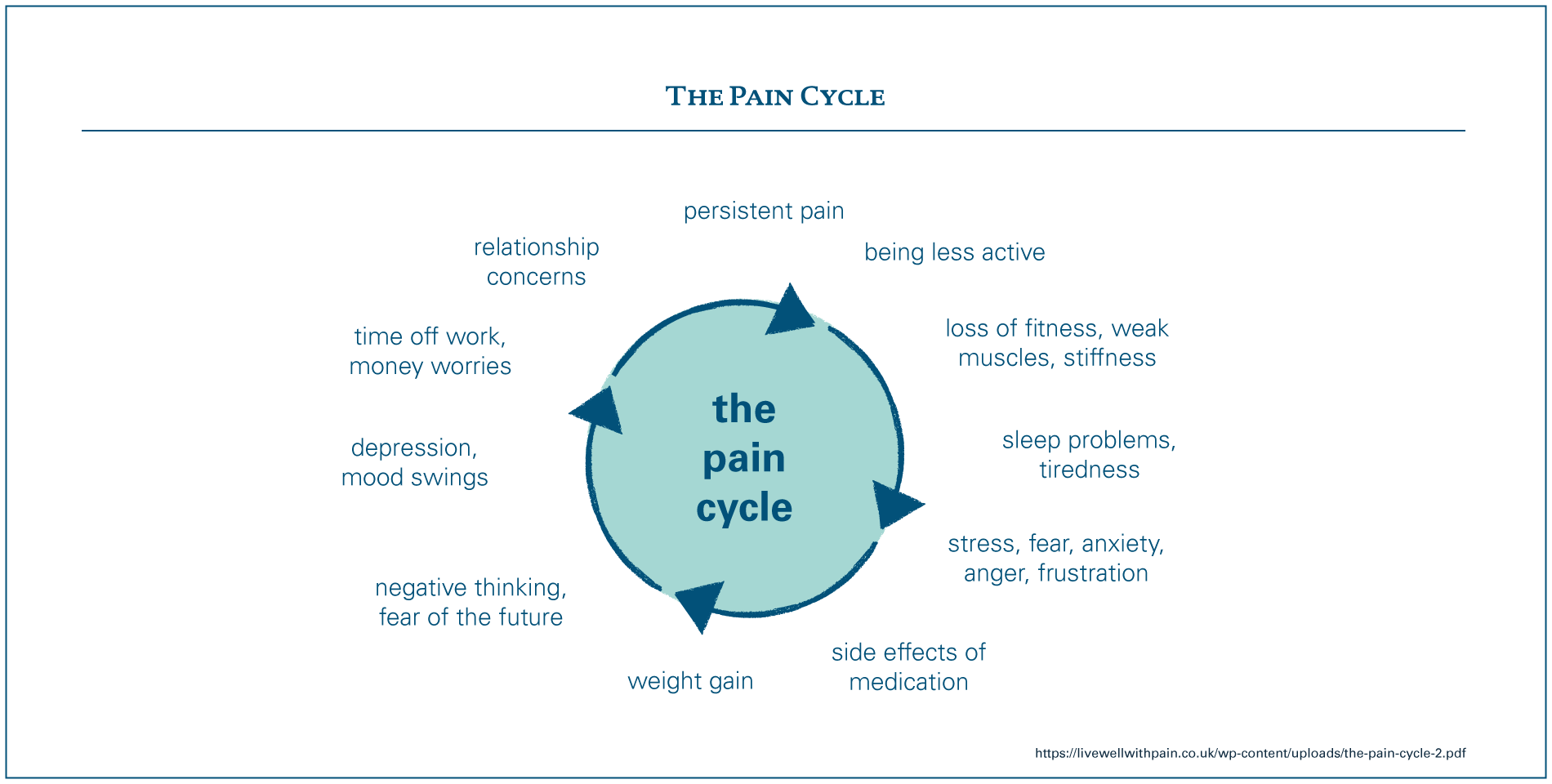

They are both issues that are made worse by social inequality: mental health problems and low back and neck pain are more common among people living in areas of high social deprivation. Both impact on an individual’s ability to work, as described in the image below, and this can put people at greater risk of poverty and exacerbates the inequality cycle.

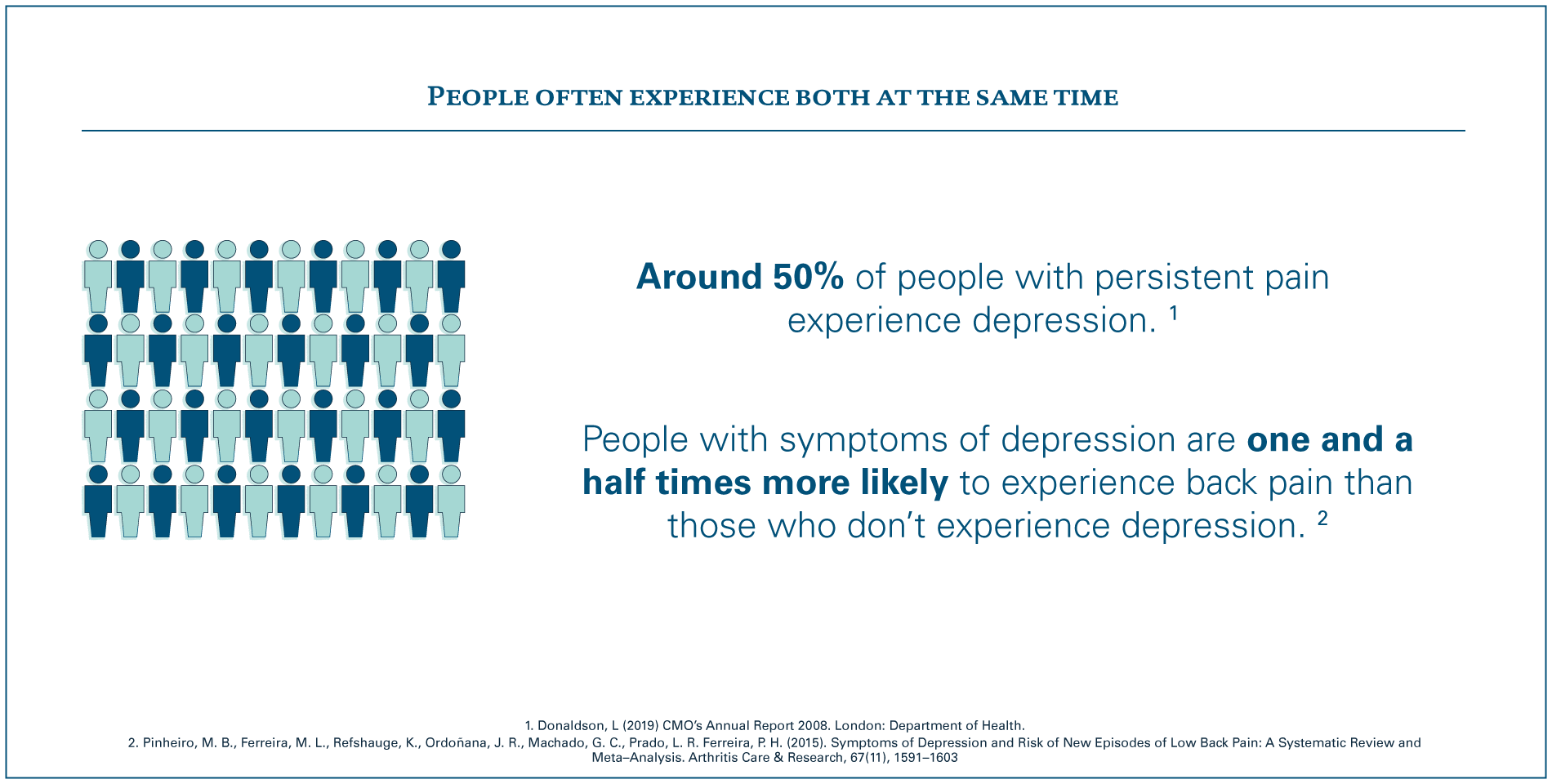

As individual health issues they present many challenges for the health and care system and wider society, and more attention is being given to them.3 However, what our work has highlighted is that it is less well known or understood that these two major health issues are linked, so people often experience both at the same time.

A two way relationship

The connection between mental health and persistent back and neck pain goes both ways: the consequences of living with persistent pain can lead to mental health problems such as depression and anxiety; and people with mental health problems are more likely to experience persistent back and neck pain than those without. This is explained by a number of biological, psychological and social factors – such as inherited health conditions, disability, confidence, coping skills, relationships and work – that interact with each other and are unique to each individual.4 5

While some people will have pre-existing mental health problems that are unrelated to the onset of their back and neck pain, the way a person experiences pain – including the severity of the pain and how disabling it is – is affected by their mental health. This in turn can affect someone’s ability to manage their pain and live well.6 7

For people living with both conditions, the interrelationship can create a ‘perfect storm’ of challenges, affecting all parts of their life and that of their family. Living with both conditions creates huge amounts of uncertainty; and can make it much harder to take up or maintain the activities and behaviours that help people to live well, and meet family, social and work responsibilities. The ‘pain cycle’ below explains how these factors may connect and reinforce each other.

The back pain doesn’t help the depression. So they are obviously connected in the fact that the physical pain makes the depression harder to deal with, because you’re dealing with physical pain as well. So it just exacerbates the condition, lack of mobility especially because I use the gym as my therapy. That’s been the hardest thing, the fact that I can’t just go and absolutely knacker myself out in the gym, because I physically can’t do that.

Interviewee

2019

Without the right support, any one or all of these issues can be detrimental to people’s health and wellbeing, their family relationships, social networks and work.

- Quality of life: People living with pain report a very poor quality of life, much worse than other long-term health conditions. It’s been reported that 16% of people with persistent pain feel their pain is so bad that they sometimes want to die.8

- Ability to work: 40% of people who attended pain clinics report that their pain has prevented them from working, and 12% have had to reduce their hours.9 Two-thirds of people with persistent pain are unable to work outside the home.10 Just under half of people responding to a Mind survey felt that their employer supported their mental health.11

Whether the mental health problem(s) existed before the person experienced persistent pain or are a consequence of living with pain, the two are intrinsically linked and will influence how someone may respond to treatment and the type of support that is needed from health services. Therefore, although the relationship is complicated, mental health and persistent back and neck pain cannot be considered in isolation.

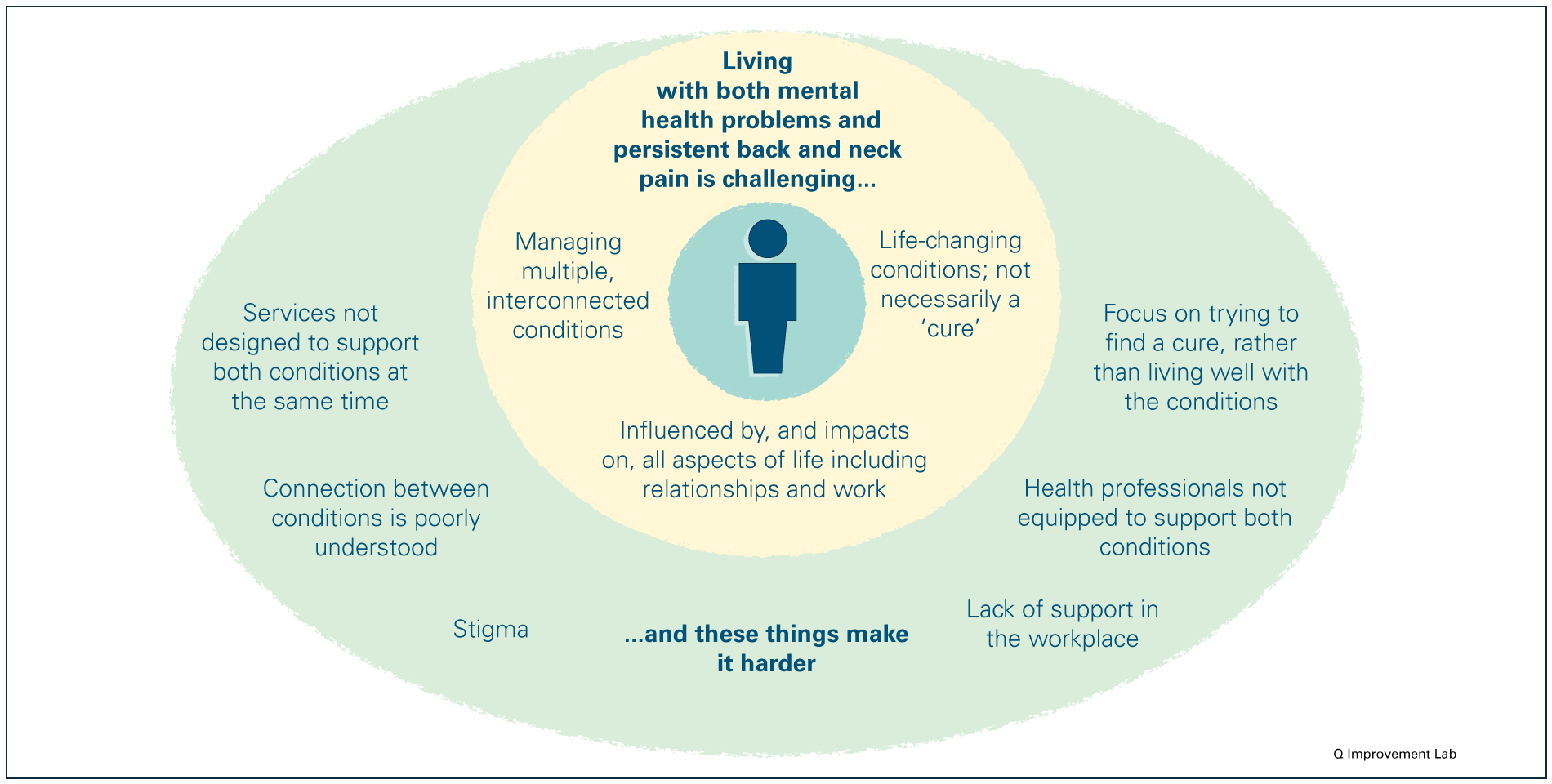

The impact of a siloed system

As living with both mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain can be challenging, may fluctuate and impact on so many areas of life, people will have different needs and expectations from health services over time. Yet the health and care system is not properly geared up for meeting the needs of people living with both conditions. This creates additional complexity that individuals must navigate in order to get the support they need.

Translating policy into practice

Mental health services have had a historic lack of investment and priority given to them relative to physical health services. This has contributed to knowledge and awareness of mental health problems and risks being low among some clinical groups.12 Pain is also often poorly understood: within the medical classification of persistent pain there is a large variety of conditions that affect people in different ways and that require different support and treatment. While it is recognised as a long-term condition in its own right, it is often a symptom of other diseases and people living with persistent pain may also live with a number of other long-term health conditions.13

Attention is being given to address some of these issues. For example, the NHS Long Term Plan for England states that the health service must become more joined-up, break down traditional barriers and provide more tailored services to support health and wellbeing.14 In Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, integrated care continues to be high on the agenda.

The impact on individual wellbeing and the high economic cost of disability and being out of work is leading to action from the Department of Work and Pensions, Public Health England and a number of national charities. There is also increasing national attention being given to the risks of opioid use, which is on the rise despite the lack of evidence suggesting this is effective as long-term pain relief for the majority of people.15

The challenges of improving care for people with mental health problems and persistent pain speak directly to this policy context. However, there is much to be done to ensure the reality lives up to the rhetoric and that people living with these conditions see positive change.

NHS England have committed to expand the availability of services for people with common mental health problems through the Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services. IAPT has been shown to positively impact people’s mental health and reduce waiting times. More recently, NHS England have begun supporting closer integration between IAPT and services for people with long-term health conditions. While the integration of physical and mental health is welcome, care must be taken to ensure that changes in service provision meet the needs of different groups. This will include people with persistent pain who may not qualify for IAPT or be best supported in the IAPT service model.16 Lab participants have also voiced concerns that the ambitious pace and scale of roll-out, and the potential knock-on effect that other services (proven to meet the needs of people with persistent pain and mental health) are not commissioned.

Despite the policy context that is encouraging integrated working and holistic care, the reality is that the structure of the UK health system and professional training is largely based around clinical specialties. Changing entrenched ways of working is slow and challenging. This means that services often separate mental and physical health care, resulting in neither service being fully geared up to effectively support people living with both long-term mental and physical health conditions.17

Disjointed services

Typically, people with mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain will access multiple separate services and see different professionals. As these professionals are often based within, and informed by, a range of organisations, policies and cultural norms, they may not provide consistency of information and care. Navigating this can be frustrating and can cause concern for someone trying to access support for both conditions. The impact of this for people living with the conditions includes:

- Feeling being ‘passed’ between services if referred to different specialist services for either your mental or physical health, or finding that your needs are not addressed. This is supported by data from the National Pain Audit, which showed that 20% of respondents who reported visiting A&E for help had seen their GP about the same problem previously.

- Falling between services and being told that either mental health or the persistent pain needs to be resolved before the other issue can be addressed, rather than addressing them as related issues.

- Feeling unsure of where to turn for help if previous treatment, advice or support is no longer working.

At the moment I’ve been bouncing between primary care and mental health and pain for the last two months. […] No one wants to take responsibility for you. Then you go to A&E and they won’t treat you at all and they say, “See your pain consultant on Monday.” You phone the pain consultant and his receptionist says, “He doesn’t have a space for the next four months.” You’re like, “What am I supposed to do?” This is what it’s like, you just get passed around and around.”

Interviewee

2019

The resulting duplication, omission or inappropriate services offered increases the cost and demand unnecessarily. It also causes harm: people may be offered services that don’t work (because they don’t address their connected mental and physical health needs), so when they finally get the service they need, it also doesn’t work. This can undermine people’s confidence in the health system and their responsiveness to treatment or support.

Workforce challenges

Due to the complex interplay between mental health and persistent pain it isn’t easy or straightforward for a health care professional to support someone living with both. While clinical guidelines have been developed and are being developed to address these issues, it takes time for cultural and structural changes to happen to enable guidance to be implemented in practice and for health professionals to overcome the siloes that prevent them from working better across different services.

It is people who have a persistent physical symptom [which often includes persistent back and neck pain] with a mental health diagnosis that we have most difficulty supporting. No one agency want to take a lead on the parts of care that is required from them. These patients have extremely poor service and they are constantly knocking on closed doors.”

Lab participant (healthcare professional)

2019

Insufficient training on mental health problems and pain among some clinical groups reinforces the dichotomy between mental and physical health and fails to equip health professionals with the knowledge and confidence to explore the interconnection between the two conditions and how this is having an impact on the person’s life. There are also structural and operational issues about the time available for open conversations to enable this assessment, and having appropriate systems and processes to support an effective referral process.

We are trying to upskill community physios to better support people who disclose mental health issues […] it’s still a shock when people say a variety of things to you. It’s not your job as a physio to unpack their history of ABC [traumas/abuse] – just about understanding the link with their recovery.”

Lab participant

2019

Culture shift

Some of the challenges of delivering integrated, joined-up services stem from historic and cultural views on health and illness. In some cases, both people with long-term health conditions and health professionals need to make the shift from seeking a ‘cure’ in the conventional sense towards being supported to live well with these conditions.

For people who develop chronic pain, there is often a difficult transition from curative medicine, into the unknown territory of ‘living well’ and ‘managing’ with a long-term health condition.18 ”

NICE guidelines

2016

For people living with both conditions, not having the right information and support to help them to understand the potential implications and impact on their long-term health can result in increased reliance on health services and affect their ability to effectively manage their own health.19

Pain doesn’t equal damage, or that people can’t live a full life. Education is the most important thing. It is about setting realistic goals.”

Lab participant

2019

For health professionals, failure to understand the interconnection between mental and physical health and seeking either a physical ‘cure’ or psychological explanation for persistent pain in isolation from each other, can result in people being referred for unnecessary clinical investigations or being offered invasive or inappropriate treatments. This cycle can result in people sometimes waiting years to get the right support and information that enables them to effectively self-manage – or getting it so late that it has a negative impact on their long-term health.20 It cannot be underestimated how challenging it is for health professionals to balance the expectations of someone seeking a ‘fix’ or cure, asking the questions to get a good understanding of someone’s individual needs, while also excluding underlying causes and avoiding unnecessary investigations.

Over-medicalisation: 80% of people with low back pain have at least one ‘red flag’, which describes signs and symptoms that could indicate a more serious underlying issue, despite the fact that less than 1% of people with low back pain have a serious underlying disorder.21 This contributes to unnecessary specialist referrals and investigations.

Ineffective treatments: there has been an increase in opioid prescribing for people with long-term pain, despite the fact that opioids have not been shown to be effective for long-term pain management for the majority of people.22

Impact of stigma

As some of the symptoms of depression and pain overlap, such as poor sleep, fatigue and poor concentration, neither issue may be recognised. While this is an issue linked with disjointed services described above, people with diagnosed mental health problems or who regularly present to health services with persistent pain, may face stigma that can lead to an inappropriate focus on their mental health.23 This can result in misdiagnosis or downplaying of physical conditions that are deemed to be psychological or are considered of secondary importance.24 This can lead to missed opportunities to provide appropriate treatment and support, distrust and anxiety, and a poor relationship between the person and their health professional.25

Quite often the pain layers on top of each other. My lower back is in pain and my [Complex Regional Pain Syndrome] causes pain. When my CRPS is particularly flared up it makes my fibro[myalgia] very bad. It gives me pain in my chest, so we’re not sure if it’s my heart or not and we end up in A&E. They look at my notes and they’re immediately like, “Yes, but it’s just anxiety.” I’m like, “Yes, but it’s pain. It doesn’t matter what’s causing it, it’s pain.”

Interviewee

2019

For individuals, their own discomfort talking about mental health is still an issue for diagnosis and treatment: people are more likely to seek support for physical health conditions and may fail to recognise or properly address their mental health needs or understand the relationship between their mental health and pain.26

Opportunities for improvement

The first half of this essay paints a picture of some of the challenges for the health and care system when it comes to improving care for people living with mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain.

Using this insight, we have worked with Lab participants to identify some promising opportunities for improvement. While some of these may sound like clichés – such as the importance of increasing awareness and training – they cannot be taken for granted, and have consistently been identified by Lab participants as key to improving care.

Increase awareness and understanding about the interrelationship

A common theme through our research is the lack of understanding about the interrelationship between mental health and persistent back and neck pain. Health care professionals and many people living with the conditions are not aware of how commonly the conditions are experienced together, or the way they may interact to impact someone’s life.

[It’s important to] normalise the responses we have to pain. Developing a persistent pain problem often comes with a lot of losses (health, self-confidence, job and friendships) and as human beings we react to loss by grieving. So many of the symptoms of mental ill health are a part of us adjusting to a change in our health circumstances.”

Lab participant (healthcare professional)

2019

If we are to make progress on improving health and care in this area, more needs to be done at an early stage so that people are prepared to accept – and expect – health professionals to consider and address both their mental and physical health. People need to be supported throughout this process, taking account of different information and support needs to improve health literacy and confidence to self-manage. This may involve formal face-to-face or remote support through health coaching, goal setting or structured information classes, or informal opportunities through peer support.

To best support this, more needs to be done to enable high quality conversations between health professionals and people living with the conditions to enable informed, shared decision-making. Clear, consistent and compassionate communication between a health care professional and an individual is vital to raise awareness of the relationships between physical and mental health; to validate their experience; to support people to accept and adapt to enable them to live well and have a good quality of life.

Research with patients suggests consultations that deliver high levels of satisfaction are those where health professionals are able to effectively convey empathy and take time to offer meaningful, resonant explanation of symptoms. A health professional’s communication skills, knowledge and experience of working with people with persistent physical symptoms can, at five key points in a patient’s journey, make a real difference.27 ”

Smithson et al – We need to talk about symptoms

2019

Increase opportunities for people to develop skills and tactics to live well

People that we spoke to who are living well with mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain had been supported to develop tactics, skills and awareness to help them manage their health with the daily challenges of both conditions. This had sometimes been enabled by pain management programmes or other health and wellbeing interventions, and at other times by people seeking out informal support through online or face-to-face peer support.

I’ve had some really positive experiences. I think the pain management programme I did was brilliant. […] I get the sense people think pain management programmes are just ways of telling people they shouldn’t go and see their GP. I really think that’s not what they are. My experience of it was it was really, really helpful.”

Interviewee

2019

Too often, services aimed at developing people’s education and understanding were the last solution and for many it had taken several years to develop their knowledge and skills to enable them to live well. This shouldn’t have to be the case: the evidence states that certain pain management interventions can achieve better outcomes and be cost-effective if delivered at an early stage.28 Accessible information and screening should be provided to identify people at risk of poorer long-term health, to enable them to access the information and support much earlier on.

Improve professional training and support to identify and meet people’s needs

Very few [health professionals] have the confidence not to do what they have usually been doing.”

Lab participant (healthcare professional)

2019

As described throughout this essay, health care professionals should take a rounded approach to assessing the health and care needs of people with mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain to understand the impact of these interrelated conditions. This is not easy, particularly with people who experience complex interrelated health and social care needs, and this is not always given prominence in clinical training. Health care professionals should have training to develop awareness, confidence and knowledge to support people with complex needs, with underpinning processes to enable implementation in practice. This can include improving pathways to better identify and assess people who may need extra support; developing tools and guidance to help clinicians signpost to other services and taking a service-wide approach, whereby training involves all members of a service or team (rather than one or two individuals).

Design services that are integrated and holistic

Health and care services that include different professions working together are better equipped to identify and support people with mental and physical health needs. While this falls within the models for integrated care that NHS services are increasingly expected to deliver, their existence is currently inconsistent and often dependent on local commissioning priorities.

Before the collaborative service was launched, the care of patients living with chronic pain could be disjointed, with each provider managing their own episode of care in isolation to other healthcare colleagues. This often led to duplication of information and multiple visits for patients.”

Dr Antoni Chan

Rheumatology Consultant at the Royal Berkshire Hospital on the Integrated Pain and Spinal Service (IPASS)

When moving to an integrated model there are lots of barriers to overcome, around IT processes, data sharing, location of services, as well as availability and funding for appropriately qualified staff. Overcoming this requires health care teams, commissioners and patients to come together to identify what needs to change. Strong leadership and a shared vision are critical.

Support people at work to reduce prevalence and impact

Providing targeted health and care information and services within workplaces can help prevent poor health and improve health and wellbeing. However, workplace initiatives to support better mental health are more likely to be reactive rather than preventative29 and the most widely promoted interventions to prevent the onset of back pain, such as workplace education and ‘no-lift’ policies, do not have a firm evidence base.30

The people coming into our programme at the moment are people who have had back pain for 10 years: they’ve given up work and it’s had a large impact on their life. If people can be referred to us just as they are developing the issue, they would get an intervention that would send them back into health.”

Lab participant

2019

While there is more evidence supporting the effectiveness of interventions that prevent reoccurrence, persistence and pain-related disability, too many people still report that their employers are not making reasonable adjustments to support them in their role.31 Furthermore, the experiences of Lab participants who provide these types of interventions suggest that sustainable funding is needed to make them more widespread.32 This suggests that workplaces need to review how they are allocating their efforts and resources to help staff stay active, productive and happy at work, and these efforts need to be underpinned by supportive work environments. We’ve heard from Lab participants how supportive organisational cultures, awareness training and peer support from colleagues can make a big difference – and how damaging the opposite can be.

I felt forced to give up my job because of the reaction of my employers to my health problems. I was employed by an organisation that was a supposedly ‘mindful employer’.”

Survey respondent

2018

What the Q Lab will be doing next

We know there is no silver bullet to meet the challenges described above: they are complex issues that require actions at multiple levels to make change widespread. Many of the issues are not specific to mental health and persistent back and neck pain: they are wider issues that will need to be overcome if the vision of integrated, person-centred care is to be realised. However, understanding these issues will be important for anyone wanting to develop and test new ideas for practical ways to improve the health and care for people living with mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain.

The Q Lab is supporting four organisations to test the assumptions and issues surfaced through this research, and drawing on examples of good practice. Together we hope to find out what it will take to implement these ideas in practice so that we can produce actionable learning to support more widespread change in the health and care for people with mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain. We will be sharing our learning on this platform towards the end of 2019. You can follow this work, and what is being learned through this process, on the Q website.

Over to you

- Let us know your feedback – what examples of good practice are you aware of that address the challenges identified?

- Start conversations – share the essay with colleagues to help build momentum and influence change in your context. What opportunities will you be exploring locally? A PowerPoint summary is available to download if you’d like a more synthesised and visual version of the essays.

- Raise awareness of the topic and share the essay with your wider networks.

If you have any other thoughts or reflections, get in touch QLab@health.org.uk