- Project one

- #2

- May 2018

Learning and insights on peer support

What we learned from the year-long project

Twelve months, one challenge: what would it take for effective peer support to be more widely available to those who need it, to help manage their long-term health and wellbeing needs?

This has been the focus for the Q Lab pilot project, involving a core team and collaboration with over 200 people from across the UK.

Peer support is incredibly diverse. It can take place in formal health care settings, in informal groups, and it often exists on the boundary between health services, charities and communities.

The Lab team spent 12 months collaborating with people who have different experiences of and expertise in peer support (Lab participants). Together we undertook research, to develop a rounded understanding of what is working well and where there are opportunities to improve and accelerate this.

This is a summary of what the Lab team heard, learned and have reflected on while working on this challenge. It is not a comprehensive review of everything known about peer support but is a summary of the Lab’s learning and insights. It builds on and refers to the current evidence and literature base1 as well as drawing on experiential and tacit knowledge about peer support, that is often unspoken or goes unwritten.

We hope this will be a useful resource for people to learn more about the current peer support context and that it will add to the growing literature around peer support, including its challenges and opportunities.

Our learning covers these areas:

- Tensions within peer support

- What is peer support?

- Peer support in the wider health and care context

- Evidence and measurement of peer support

- Making peer support more widely available and accessible

- Where next for peer support?

Tensions within peer support

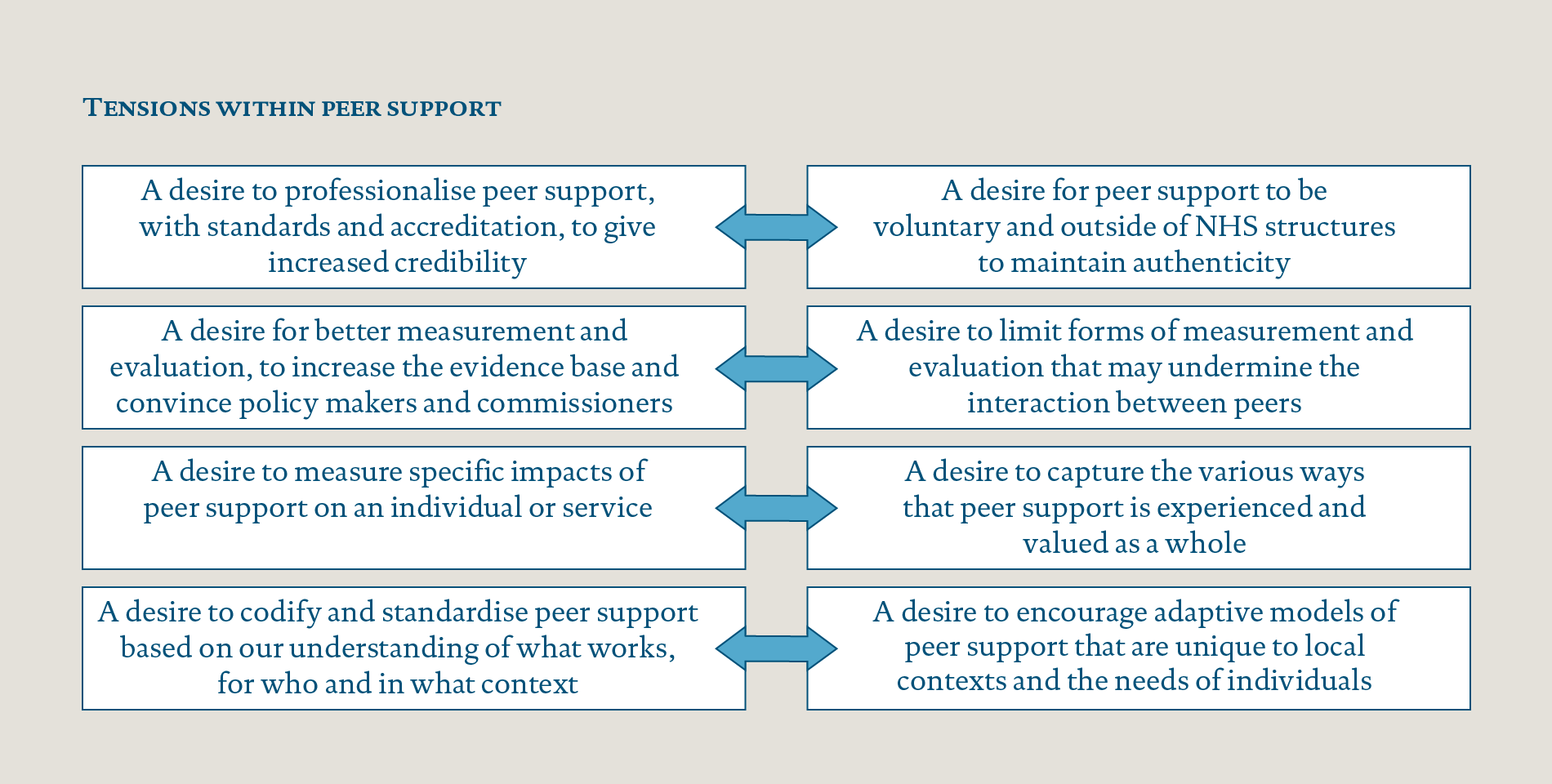

This essay highlights and draws attention to some of the tensions that exist in peer support. These tensions are known to people working in this field and through the Lab process these have been surfaced, discussed and debated. The tensions may not be possible to resolve as they represent different views about desirable futures for peer support. These tensions include:

Throughout this essay we will refer to these tensions.

What is peer support?

Peer support in health and care is where people with shared experiences, characteristics or circumstances support each other to improve health and wellbeing. Peers can be people with similar health conditions, or from similar communities or backgrounds.2

Peer support can take many different forms – both inside and outside of formal health services. Some peer support is provided by NHS organisations, most commonly in mental health; sometimes it is commissioned by the NHS and provided by a wide range of organisations, often with charities leading the work; and at other times it is completely self-organised.

This variety of peer support has implications for how it is understood and delivered. The term ‘peer support’ can be used to cover a range of activities. This can cause misunderstanding, complexity in how to measure and evaluate peer support, and difficulties in how people become aware of and access services.

Values that define peer support

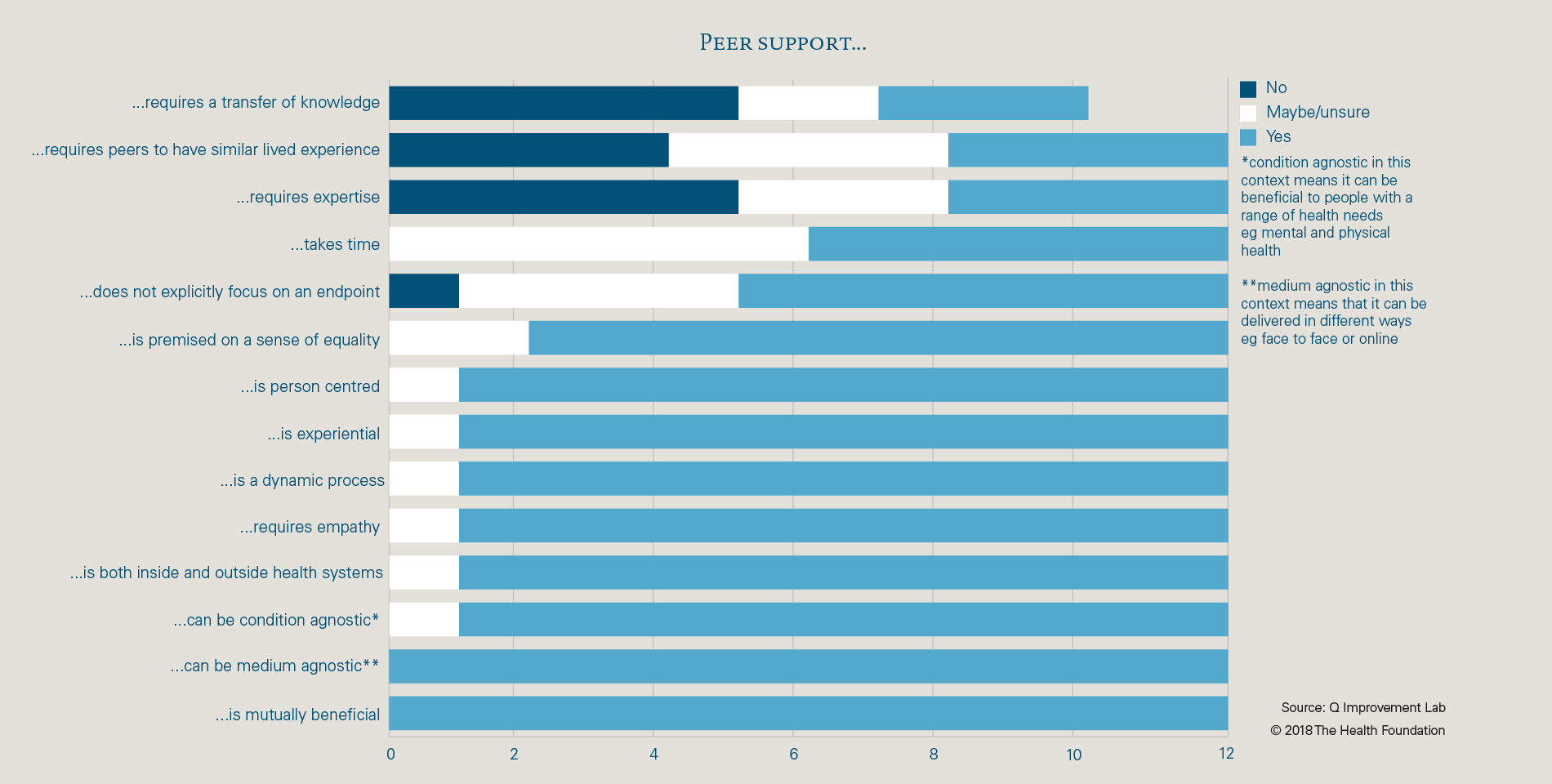

While there is no standard model of peer support, there are some inherent principles that are shared. As part of the Lab research, we interviewed people who have different experiences of peer support. We asked interviewees to respond to a set of value-based statements regarding peer support. The following chart summarises how people responded.

This chart highlights the areas where there was agreement between interviewees about the values of peer support, for example agreeing that it is mutually beneficial and can benefit people with a range of health conditions. There was more disagreement on the final three points, about whether peer support requires expertise, similar lived experiences and a transfer of knowledge. There were mixed views about whether peer support takes time and focuses on an endpoint, which relates to the different modes that peer support can take.

This exercise shows that there are some clear values and principles underpinning peer support, despite the different forms and practices.

Peer support in the wider health and care context

Over the past 15 years, interest has been growing in the UK and internationally about how health and care services can put people at the centre of their care, and support them to become active partners. In the UK, much of this work sits under the banner of person-centred care, personalisation, or choice and control. There has been a focus on increasing choice and supporting or empowering people – particularly those with long-term conditions – to better manage their health and care (for example, through the Expert Patients Programme and other approaches to self-management support). As argued by Alan Cribb in his recent book, the development of health policy that values personalisation, brings with it philosophical change in our conceptions of health care, as clinical concerns are increasingly nested within social concerns.3

Until recently, peer support has been largely absent from policy recommendations, although this is starting to change. Peer support has received significant attention in the Realising the Value programme that was commissioned by NHS England and delivered by Nesta and the Health Foundation with partners across the UK.4 The growing focus on social prescribing offers another route for access to peer support, by connecting people with support offers in their local communities.

The NHS is under financial pressure and funding for peer support is variable. The Realising the Value programme advocated investing in self-care and approaches like peer support as part of a long-term solution to current pressures, while recognising that funding decisions are complex. The evidence that peer support improves health and wellbeing is strong, but the evidence that it will improve NHS sustainability is mixed.5

Mental health policy context

Peer support is more widespread in mental health services; it has been central to the development of models for recovery in mental health and therefore the literature and evidence base is more developed than for physical health services. The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health explicitly mentions the value placed on peer support and the need to focus on continuing to build the evidence base.6

There is however further work to be done within mental health, particularly in relation to the peer support workforce. Health Education England has identified developing and supporting peer workers as an important part of the future mental health workforce strategy, and an area where more attention and investment is needed.7

Voluntary and charity sector in peer support

The voluntary and charity sector has a significant role to play in peer support in the UK, delivering some of the largest and most successful approaches. These have often started outside the NHS and, as they have matured and grown, have found ways to work alongside traditional health and care services. An example of this is Positively UK, which was started in the 1980s by two women who had been diagnosed with HIV. They felt that existing health care services were not meeting their needs so they set up a service with a peer led ethos. Positively UK has a vision for 100% of people diagnosed with HIV to have access to high quality peer support and recently supported the development of National Standards for Peer Support in HIV.8

Tensions in the wider health and care context

Peer support sits at a boundary between formal, statutory health and care services and community-based support. As such, there is a question of whether it should be driven formally from within the system, or supported to grow in a more organic, informal way by communities. Some Lab participants have spoken of their concerns about peer support becoming too embedded within formal systems and the risk that the essence or principles of peer support will be lost. Other Lab participants feel that unless peer support connects and integrates more with other health services it will never become as widely available as it could. Research shows that peer support is most effective when:

- underpinned by values and principles that recognise people’s resources and potential

- driven by what people want and need

- co-produced and provided by people with experience of living with the condition

- it establishes a culture of mutual benefit and sharing experiences with each other as equals.9

The fact that peer support establishes a culture of mutual benefit can set it apart from other health services that are based on a ‘professional’ and ‘client’ interaction. This connects to the tension between professionalisation and authenticity. In providing peer support, there may be different priorities or ways of working. When doing this inside or alongside an organisation with established ways of working it can cause conflict or undermine the essence of peer support.

I think sometimes the peer support workers question the value of what they’re doing. I think because we work in a service that is all about fixing and doing things. A peer support worker is about being and learning, and then it’s difficult if you’ve got a very different approach, to see the value of that in the face of a whole service that’s working in a contrasting way.

Interviewee

June 2017

When peer support is provided by the voluntary and charity sector, peers can be unpaid volunteers. This fits well with the principle of peer support being mutually beneficial and creating an ‘equal’ relationship. But it can also lead to the view that peer support can be provided for free or for very little cost. There are important questions about how sustainable or widespread peer support can be without secure funding.

If the vision for the future is to increase the provision and uptake of peer support services within health care settings, it will be important to create spaces in which to explore these areas of complexity, and to provide support to help people navigate them. There remains little reference to peer support in education and training for health and care workers, which would be one route to surface these tensions.

Evidence and measurement of peer support

There is a wide range of evidence that demonstrates the benefits and effectiveness of peer support on physical and mental health. Peer support can help people to feel more knowledgeable about their condition, to be more confident and happy, and to feel less isolated and alone.10 The evidence is strongest for people with long-term health conditions such as diabetes or with mental health issues. This does not necessarily mean that the benefits are limited to people with these conditions, and may instead be a reflection of where research to date has largely focused.

There is growing evidence of the economic benefits of peer support and its wider social value; it can impact how people use health and care services and can lead to wider social outcomes such as helping a person return to work or education.11

Evaluating peer support effectively

Despite the promising evidence base, there is a debate about whether we need to move beyond traditional models of evaluating health and care to understand the full benefits of peer support.

Methods that have traditionally been used to evaluate health care interventions to provide high quality evidence, such as randomised controlled trials, may not be best suited to evaluate the impact of peer support. The impact can be wide ranging, touching on different aspects of people’s lives. Often peer support is one element of the care or support people draw on, therefore it is hard to attribute impact directly and solely to peer support. Its benefits may also extend to other parts of the health and care system, beyond benefits to the individual, which can be hard to track.

This challenge is being felt in other fields such as public health, and was the topic of a Health Foundation event in February 2018. The event brought together leading experts from a range of industries to discuss ways to diversify the evidence that is used to assess public health issues. The discussion focused on how to put the individual at the centre of research and increase the value placed on evidence derived from lived experience.12

There is an opportunity to develop and use more suitable evaluation and research techniques that can demonstrate the impact of peer support and supplement other forms of evidence that are currently being used.

Some Lab participants wanted to better understand what type of peer support works best for whom, and in what circumstances. This connects to a live discussion about whether this is possible or the most valuable area of research. A recent evaluative study has suggested that choice and control of the way people access peer support is more important than the service model itself, and that people more commonly pick and choose the peer support that works for them rather than following a structured programme that is more suited to comparative studies.13

There are different views about whether to prioritise evaluation techniques that capture specific impact on individuals or to evaluate the wider benefits that are derived from peer support. In the following sections we discuss these different routes to impact.

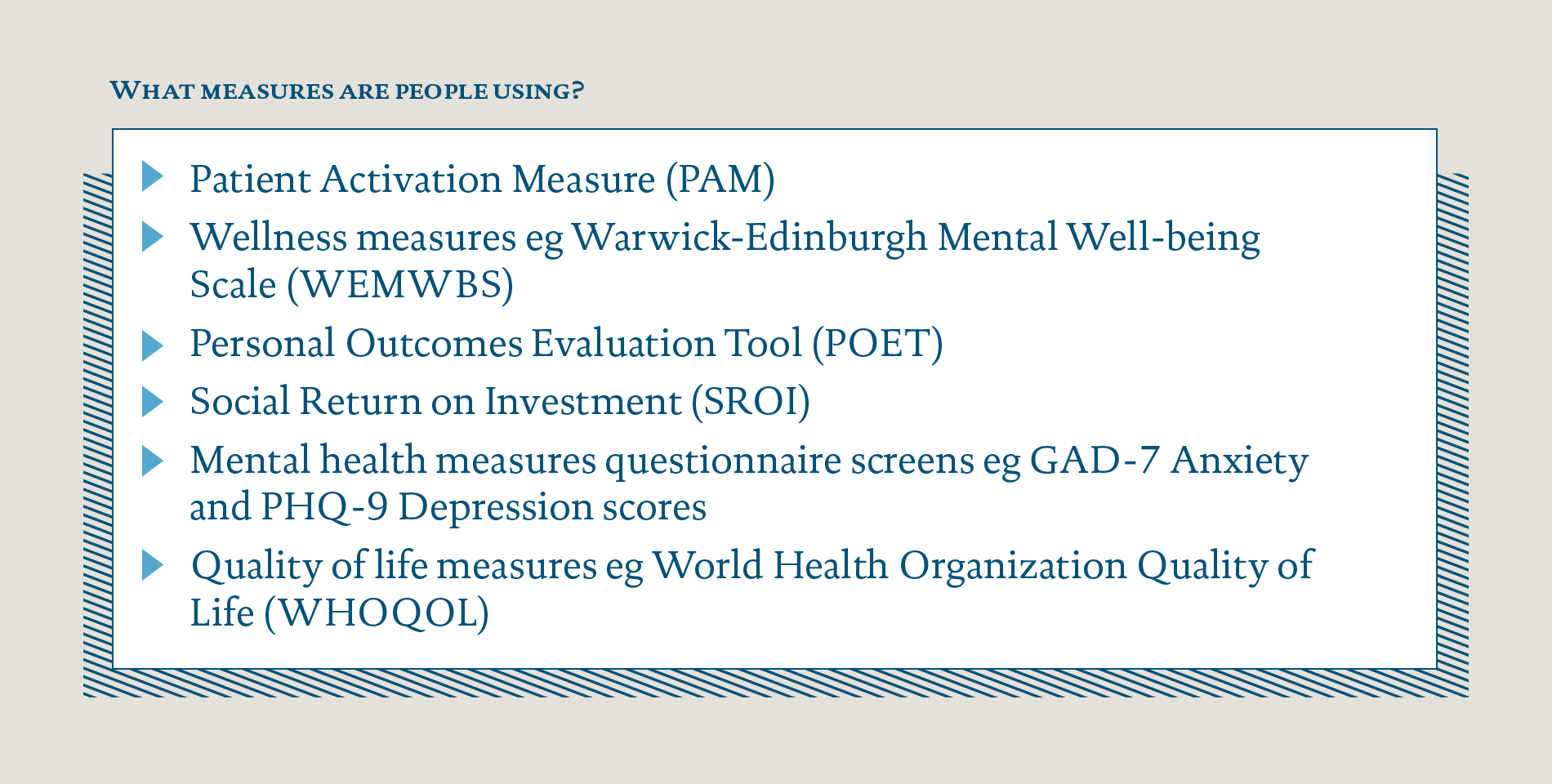

Choosing evaluation metrics

Services are using a range of different measures and metrics to demonstrate impact. Those working in peer support told us that they felt these under-represented the wider impact of peer support, for example helping someone return to work, or supporting carers or families to improve their own wellbeing. There is also a tension about how to add data collection to peer support in a way that doesn’t undermine the core values.

There isn’t an embedded way of evaluating peer support in the organisation… It’s something that we need to get better at, but there is that… worry that any data collection in a peer relationship… transforms that peer relationship.

Interviewee

June 2017

The metrics that services are using focus largely on individual health and wellbeing. They often provide indications of clinical outcomes, as opposed to drawing out what people have experienced and valued.

Within the NHS, there is also the need to collect data against system measures such as reducing A&E visits or unplanned admissions.

From the Lab’s interviews there were suggestions for what could be measured, to provide supplementary data about the benefits of peer support. Suggestions included increased uptake of social prescribing, people who go into employment or volunteering, or experience and feedback scores.

Novel approaches to research and evaluation

Lab participants and workshop attendees often stated that the benefits of peer support are most fully captured in individual stories and personal insight. It can be difficult to integrate these findings with more traditional forms of quantitative and qualitative evidence that services are asked for, such as health outcomes measures and economic evaluations.

Participatory research was highlighted as an opportunity to build the evidence base in a way that is better suited to peer support. Participatory research focuses on the ‘subjects’ of research being involved in the activity of research and is founded on collaborative principles. The recent evaluation of Mind’s Side by Side programme – undertaken by St George’s University of London, the McPin Foundation and the London School of Economics – used this approach and involved 100 interviews and data from 700 questionnaires.14

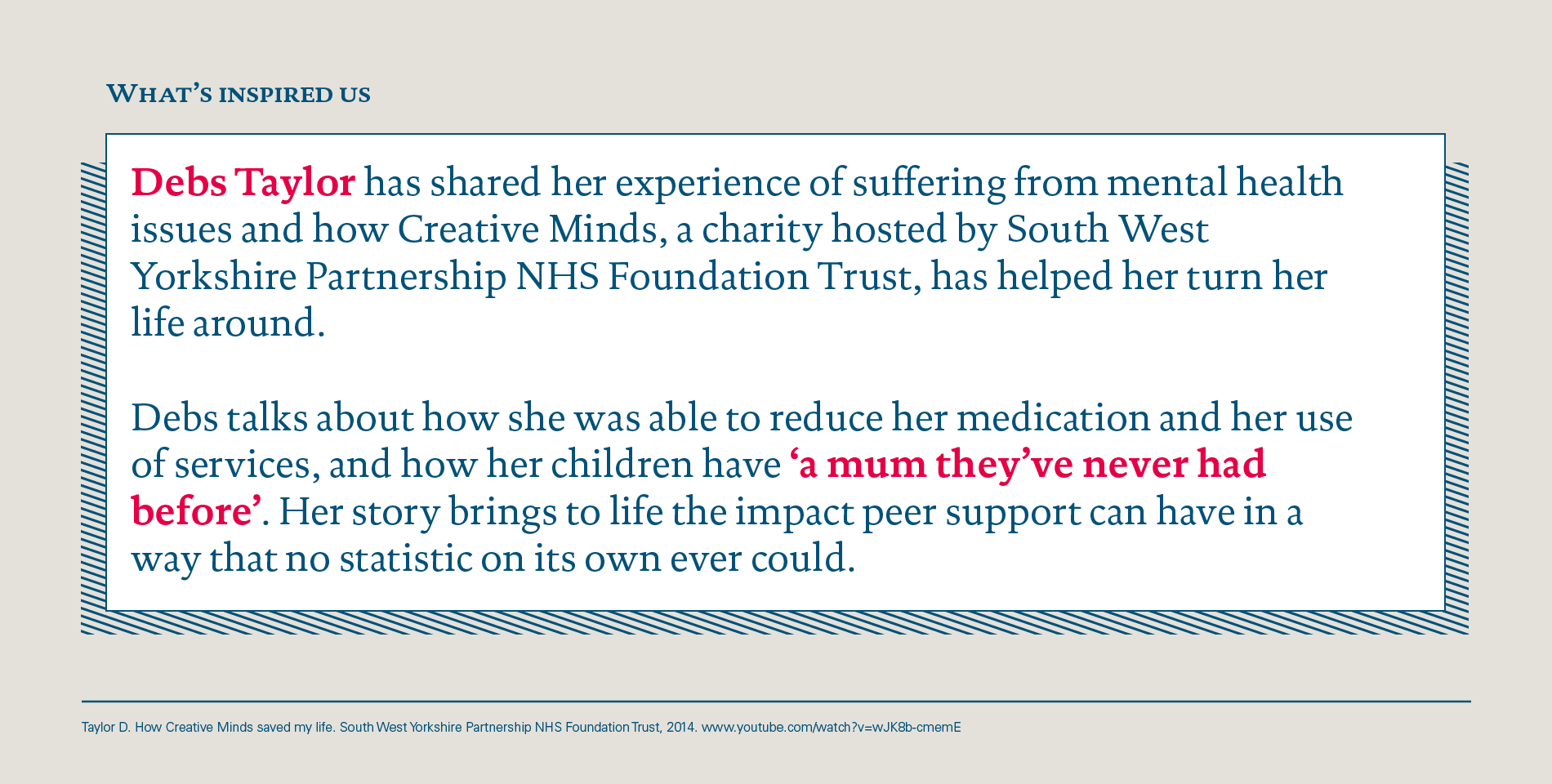

Attendees at the Q Lab workshop in July were interested in using storytelling to both build the evidence base for peer support and enable lived experience to play a bigger role in decision making and commissioning of services. They cited a growing number of examples of how storytelling is already being used to communicate impact in a different way, for example the 100 Stories of Co-production initiative in Scotland.15

This led us to do further work into the opportunities of storytelling; to understand how it’s being used, by whom and for what purpose. We sought examples of learning or good practice and have pulled together some links and resources that may be helpful for others.16

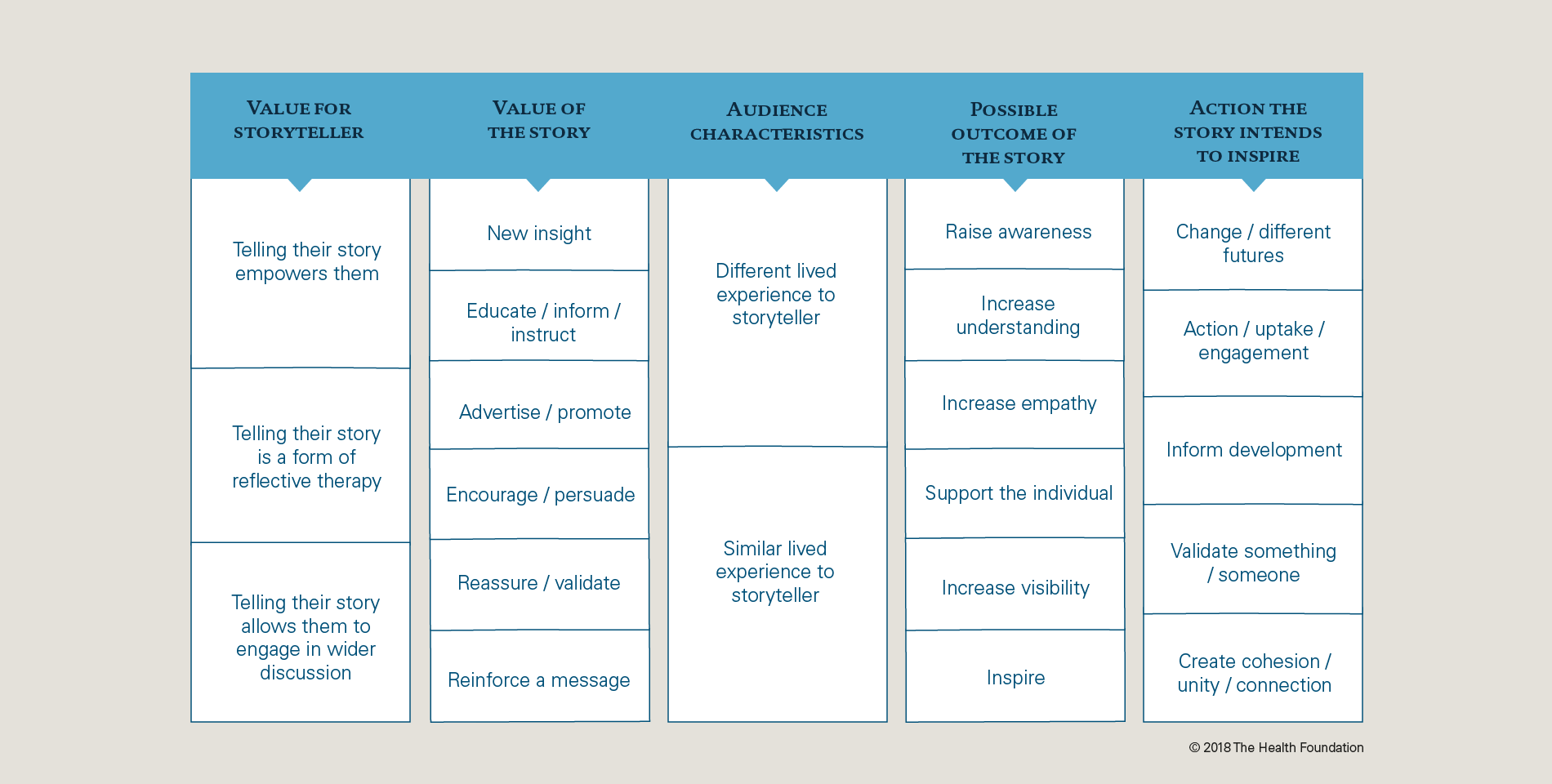

We developed a prototype storytelling topography (as shown below) to help us to understand how storytelling was being used. We believe the topography could be helpful for others when thinking about using stories to bring about change. It sets out the different categories of how stories are being used by separating out the value for the storyteller, value of the story itself and potential outcomes and actions that it intends to inspire.

The effectiveness of storytelling in inspiring action is not fully understood. Through the Q Lab survey on decision making (that’s described in the How do people make decisions in peer support? essay) we asked people to rank what’s important to them when making decisions around peer support. People reported that they do not value stories from people who have used peer support as highly as other factors, such as evidence about the impact of peer support, or the belief it will improve health and wellbeing. It’s unclear from the findings whether this is down to people’s perceptions about stories, and whether they would be influenced by stories if they included evidence of impact and improvements to health and wellbeing.

Evidence Hub

The Lab frequently heard that research and evidence for peer support is not always well-used. Through Q Lab workshops and a separate event in July 2017 (led by National Voices, Mind and Positively UK) an opportunity was highlighted to gather peer support evidence into an online hub that could be a long-standing home for this information.

National Voices and the Q Lab have worked together to design and scope this opportunity, with support from Mind and Positively UK. The Hub will help inform and guide people and services who deliver or would like to deliver peer support. It will bring information, insight and evidence sourced from different areas together in one place, including published and community generated content. By making this information more accessible, the Hub aims to support the development of more effective peer support in the UK, and will help to build the case for peer support.

National Voices will take this work forward and will launch the peer support Evidence Hub in 2019.

Making peer support more widely available and accessible

The terminology used to describe peer support is often inconsistent, which can make it difficult to understand what a service might be able to offer or how it compares to other services. There are challenges, therefore, in how to engage the general public in seeing and using peer support as a way of helping them with any health conditions they may have.

A survey of GPs by Nesta showed that 61% are not familiar with what peer support services are available in their local area.17 Some organisations and locations have tried to address this by developing signposting tools such as the peer support directory developed by Mind for mental health services in England.18 Others, such as Macmillan, have embedded peer support alongside other services. An impressive 83% of cancer patients who responded to the annual patient survey in 2015 said that hospital staff gave them information about support or self-help groups.19 It could be an interesting area for future research to understand more about what has driven this, and whether there is replicable learning for other services.

Peer support may not suit everyone. When people are offered peer support, the level of choice and control they have in deciding what to use, when and why is associated with positive outcomes.20 For some people, peer support is needed when they are first diagnosed with a condition. For others, the right time could be further down the line when they want to change their approach to managing a health condition. This difference in when peer support is needed makes it difficult to design referral pathways that have been used in other areas of health care to improve uptake.

In addition to getting the context and timing right, it is important that people can choose peer support which is tailored to their individual needs – not just in relation to their health and wellbeing, but also their cultural, religious and social backgrounds.

Utilising and increasing capacity for peer support

Many health care services in the UK are at capacity. We have heard that this is not always the case with peer support. Some Lab participants report having unused capacity or underutilised services, in part caused by a lack of awareness that the service exists. Even services that have been commissioned and can show a positive impact on people’s lives report this problem. We found that people are having to be creative in seeking new ways to get their services known about and understood.

Individuals may discover some peer support through social media or online searches. Other services are less likely to be found this way and rely on signposting from a health care professional. The pressures on primary care clinicians – GPs in particular – can mean that a short consultation may not always be the best place for a discussion of peer support. Often as part of wider social prescribing programmes, practices are employing care navigators – professionals who support people to access care and support services that meet their needs – to ensure there is dedicated time and space for conversations such as these to take place.

During the Q Lab project we have been contacted by over 200 people who are interested in peer support. A significant proportion of these enquiries have been from people who are interested in setting up a new service. This interest is really encouraging for the future of peer support, and provides an opportunity to make sure that useful information is available to help people on this journey.

Information is available online and example guides include:

- Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change (ImROC) Briefing no.7 – Peer support workers: a practical guide to implementation

- Mind – Developing peer support in the community: a toolkit

- Peers for Progress – Peer support resources

- Mental Health Foundation – Peer Support Manual

- Centre of Excellence in Peer Support – Online resources

We have found that there is interest in learning from people’s practical experiences of peer support which is not always reflected in the information available. Lab participants have cited this as one of the benefits of being involved in the Lab process, and it has been a regular discussion point at workshops. There is an opportunity to better signpost people to different models of peer support and share more widely the operational challenges that people have overcome when delivering peer support services.

Interest in online peer support offers

There is growing interest in developing online peer support offers. In 2017 a survey of 3,700 people indicated that 96% of 16-24 year olds reported owning a smartphone – illustrating the direction for technological literacy rates.21 There is therefore real potential in expanding the online offers for peer support. Discussions at Lab workshops have highlighted the opportunities in having a space that can be accessed as and when you need it, and is available to many people.

…I am involved with a peer support group which started meeting face to face in Glasgow but because people were desperately looking for support people ended up travelling from as far away as the Highlands to attend it. The Facebook group was set up to try to in some way to reduce the need for travel and to allow people to access peer support at times outside the face to face meeting and it has achieved both those aims. In addition, we have found that people who joined and then discovered they were geographically nearer others have now gone on to start their own local face to face groups… The USPs for us were that it allows people to access peer support even when they are geographically isolated from others. It is also a great way of sharing info, petitions and campaigns. In addition, there is a high level of privacy for group members.

Ann Innes, Lab participant

March 2018

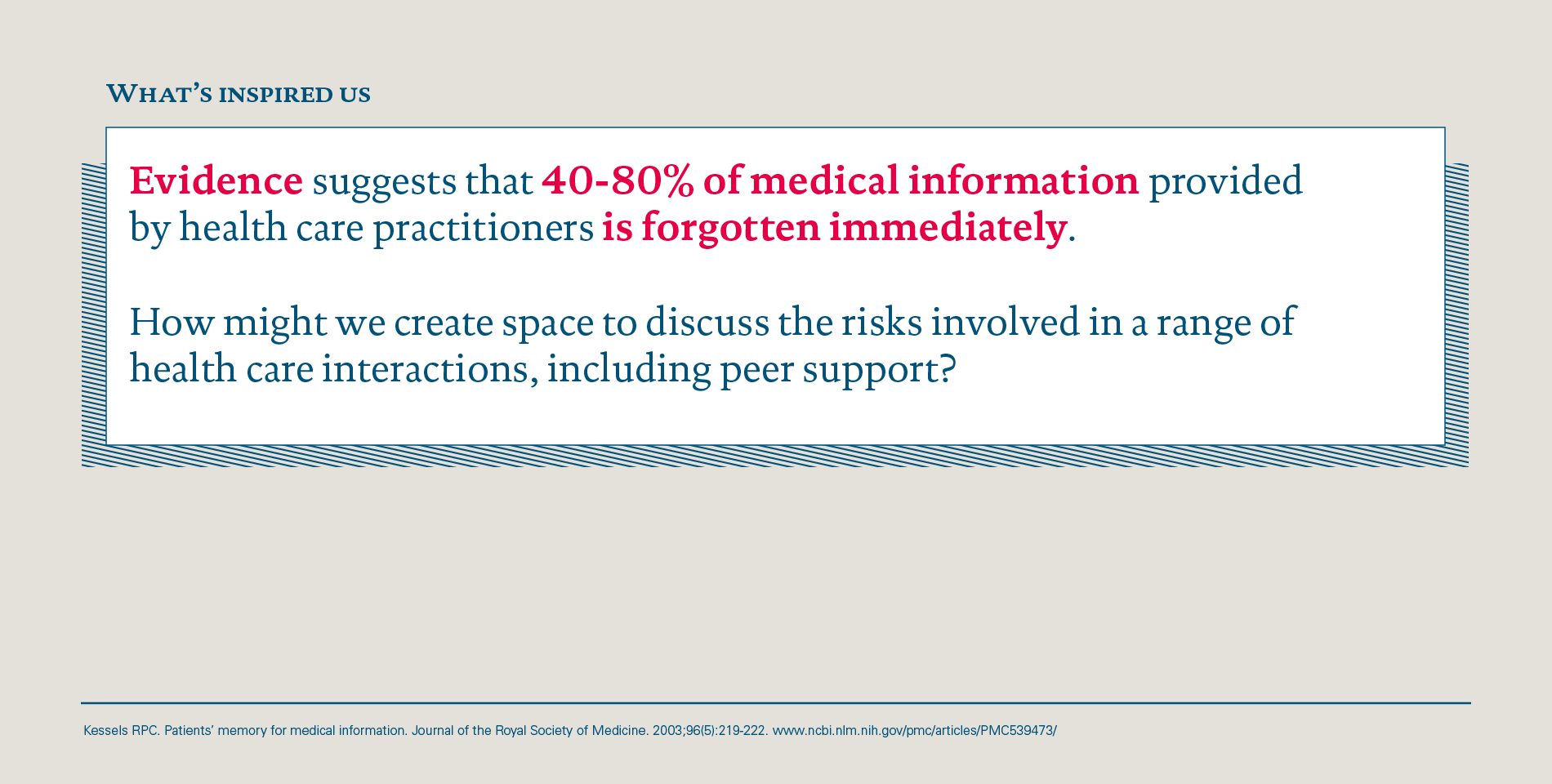

We have also heard about the challenges, such as controlling who can join the group and understanding how to manage the risk attached to unregulated advice. It may be the case that this risk has been overstated, with recent research suggesting that misinformation is often corrected by peers in an online group.22

Undoubtedly, setting up online groups poses questions and challenges to those responsible for the platform, and to the wider health care profession about how this technology can sit alongside traditional health and care service provision.

We have heard stories about peer support done badly, or instances that have caused concern. It is important that people who are involved in peer support have the space to talk about these examples and to share their learning, without worrying that it undermines the premise for peer support altogether.

Understanding decision making in peer support

We identified that there was little research that sought to understand what mattered to people when making decisions in peer support, such as whether to recommend, refer or access it. Given the broader issues on access, this felt like a productive area to study. The Q Lab therefore undertook a large-scale survey of over 2,500 people exploring this issue.

The survey allowed us to learn about what is important to the health and care workforce, peer support workforce and the public when making decisions about peer support, highlighting the similarities and differences between these groups.

Findings from the survey might influence communications, decision making and behaviours around peer support and contribute towards improving promotion and uptake.

For the full survey findings, read the How do people make decisions in peer support? essay.

Where next for peer support?

The Q Lab challenge was to understand what it would take for effective peer support to be available for everyone who needs it, to help manage their long-term health and wellbeing needs. Through the process of collaborating with over 200 people and undertaking in-depth work over a 12-month period we are able to describe some of what is needed to achieve this ambitious aim.

The conversation needs to move beyond whether peer support works. Measurement will always be necessary, in continuing to identify more or less successful practice, but it is important to acknowledge the evidence that exists. More attention should be given to the barriers to widespread take-up of peer support.

Acknowledging and surfacing the tensions in peer support

Throughout this essay we’ve highlighted some of the tensions that exist in peer support: between professionalisation and authenticity; bringing evaluation into a relationship based on equality; focussing on large-scale impact or individual experience; codification and adaptivity.

These represent some of the unspoken challenges that exist in the widespread take-up of peer support, and will be common in other areas of person and community centred care.

In order to achieve transformational change in the ways that care is provided and received it is important to acknowledge and surface these tensions, and collectively propose routes forward.

Increasing awareness and understanding

There doesn’t appear to be widespread understanding and awareness about what peer support is. This is complicated, or perhaps demonstrated, by the absence of a single definition that is shared by many. The findings from the decision-making survey help to identify how messages could be tailored for different groups. Programmes should be developed to raise awareness with people who could benefit from peer support, or who may be inadvertently ‘blocking’ access to it.

Ideas for how to address this include:

- Building on Peerfest (the annual celebration of peer support) by having a national peer support day where people pledge to spread the word or take part in peer support activities.

- Running awareness campaigns in public spaces.

- Testing interventions with health care professionals who are well placed to introduce peer support to people, such as pharmacists or paramedics.

- Testing different ways to introduce peer support to people, using the findings from the decision-making survey.

Building a thriving community of interest

We’ve seen that there is a growing interest in peer support from people working in health and care. The peer support community should take advantage of this wave of interest by having more spaces for people to share their experiences, surface some of the unique challenges and develop a shared understanding of best practice.

Ideas for how to address this include:

- The online Q Lab group on peer support continuing as a space that facilitates open discussion and learning.

- The Evidence Hub being used to champion peer support, so people can share and use information and insights more effectively.

- Developing training tools that recognise the multiple forms of peer support.

- Bridging the gaps between charities and health care providers to work on developing peer support together.

Supporting changes to the way peer support co-exists with health and care services

If peer support is going to be widely available it will require changes to the way that current health care services operate. The cultural challenges in achieving this shouldn’t be underplayed, which relate to how staff are trained, how risk is managed, how lived experience is championed and how expertise from the voluntary and charitable sector is utilised.

Ideas for how to address this include:

- Learning from the successful examples where peer support has become the norm in care delivery, such as in HIV and cancer services.

- Supporting health care professionals to understand the values of peer support, and providing space for conversations about how this interacts with existing services.

- Developing roles for people with lived experience to work alongside or as part of existing services (either employed or voluntary).

- Trialling service models that put peer support interventions at equal prominence to clinical interventions.

The Q Lab is founded on the principle that bringing different perspectives together, to interrogate existing data and evidence, allows us to surface new understanding on a topic. Research has shown that improvement projects in health care often fail because they don’t allow sufficient time at the beginning to bring stakeholders together to discuss the problem that they are aiming to address.23

In the past year we have benefited from countless interactions from Lab participants. People from all across the UK have contributed, bringing their passion and enthusiasm to the work. There has been an openness to explore the topic area, to challenge each other and to learn.

The process of meeting and connecting with people across different parts of the peer support spectrum has led to increased understanding, a clearer sense of the shared values and, in some instances, has facilitated a shift in views.

We have seen and heard how peer support can embody different values and principles. There have been lively debates about how peer support can ‘fit’ alongside other parts of health and care, or whether it should form part of a ‘revolution’ in health care delivery. The Lab process has sought to accommodate these different views, to hold the tensions that exist rather than resolving them. In involving a wide group of people in this process, we have learned from each other and developed a greater depth of knowledge and understanding in the topic.

This essay describes the evolving context within which peer support exists in the UK health and care system, and its prospects for the future. It reflects what we have learned, heard and reflected on over the last year. It can be used to prompt discussions for people who are looking to set up, improve, evaluate or commission peer support services in the future.

If you’d like to find out more, join the Q Lab peer support online group.