- Project one

- #3

- May 2018

How do people make decisions in peer support?

Understanding what's important when referring, recommending or using peer support

During the Q Improvement Lab (Q Lab) pilot project, the Q Lab carried out a nationwide survey on decision-making in peer support; we believe it to be the biggest peer support survey in the UK. It provides valuable insights both about the current awareness and uptake of peer support, as well as new information about what matters to people when deciding to either access peer support or refer/recommend peer support to others.

The Lab quickly identified that, while there is a body of evidence about the impact peer support can have on people’s lives, there is little evidence about why people access peer support in the first place, and what factors influence the likelihood of them doing so. Similarly, the Lab’s work found that there is little evidence about what matters to health care professionals when deciding whether to refer or recommend peer support services, and what they might need when making this decision.

This essay describes why and how we did this research before presenting the full set of findings and how they might be used by people working in or with peer support services.

Why is this peer support survey important?

Supporting and enabling people to access peer support can be challenging. The Lab identified a range of issues linked to this including: lack of information about available services, low referral rates from health care professionals, and poor uptake due to personal, social and cultural barriers or a belief that peer support will not help. (Read the Learning and insights on peer support essay for further information.)

When we explored some of these access issues further, we identified that there was little research that sought to understand what really matters to people when deciding whether to refer to or use peer support. By understanding what influences people’s decision making around peer support, we can make progress on some of issues with accessing peer support as listed above.

We carried out a peer support survey to understand more about the priorities of three different groups of people: the health care workforce, peer support workforce and the public. Our hypothesis was that if we know more about what matters to people when they are referring to, recommending or considering accessing peer support, this may deepen our understanding of behaviours in peer support, improve the conversation between different groups of people and so improve access to and uptake of high quality peer support.

Who and what did we ask?

We asked each of the three groups below to think about what was most important to them when making decisions around peer support.

The health care workforce: We asked them to think about what was most important to them when deciding to refer people to peer support. We identified difficulty in engaging health care professionals as a major barrier to referring people to peer support. Therefore, to improve referrals to peer support services, it is important to understand what the health care workforce need or would value in order to refer people to peer support services.

The public: We asked them to think about what was most important to them when deciding to use peer support. Peer support is unlike many other clinical interventions in that it is available to all without a prescription. As potential users and beneficiaries of peer support, it is crucial to understand the viewpoint of members of the public.

The peer support workforce: We asked them to think about what was most important to them when deciding to recommend people to peer support. Those working in peer support, who often also have experience of using peer support, are responsible for advocating and promoting their service and its benefits. We wanted to understand what they consider to be most important when recommending peer support to others.

Designing our research approach

A study has recently been carried out in the United States which used novel analysis to assess the priorities of Republican and Democrat politicians in relation to national health policy in the US.1 By using a similar approach we were able to identify the extent to which people disagree or agree on the importance of different policy goals, and therefore what issues might be most suitable for cross-party collaboration.

We thought these same methods could help us to understand the value of different factors to different groups of people in relation to peer support. We worked with Lab participants and other key stakeholders to design, develop and test the peer support survey. The main question in the survey asked respondents to rank a list of factors, from most important to least important, when they were either referring to, recommending or accessing peer support.

The list of factors was co-designed with Q Lab participants and covered a range of different priorities that were distinct, and would be applicable to the broad audience which the peer support survey targeted.

We tested the survey with Q Lab participants, members of the public and with people face to face at the UK-wide Q community event and Peerfest, an annual peer support festival. The testing phase highlighted the importance of clear, non-technical language as well as a concise list of factors to rank.

The final 12 factors were:

- An opportunity to meet people with similar experiences

- Evidence that the service makes a positive impact

- Belief that attending will be a rewarding experience

- Belief that it would improve health and well being

- Knowing that peer support can be used alongside other health services

- The service being easy to access

- Being able to find out details about the service

- Ability to access the service quickly

- Confidence that the service is safe, confidential and high quality

- Stories from people who have benefitted from the service

- The service being endorsed by a health care professional

- Reducing burden on the NHS

How we analysed the peer support survey responses

The final peer support survey contained seven questions. Six questions asked respondents about their role in and interaction with peer support, including whether they identified as having a long-term condition and other demographic questions. The final question was the ranking question, described above.

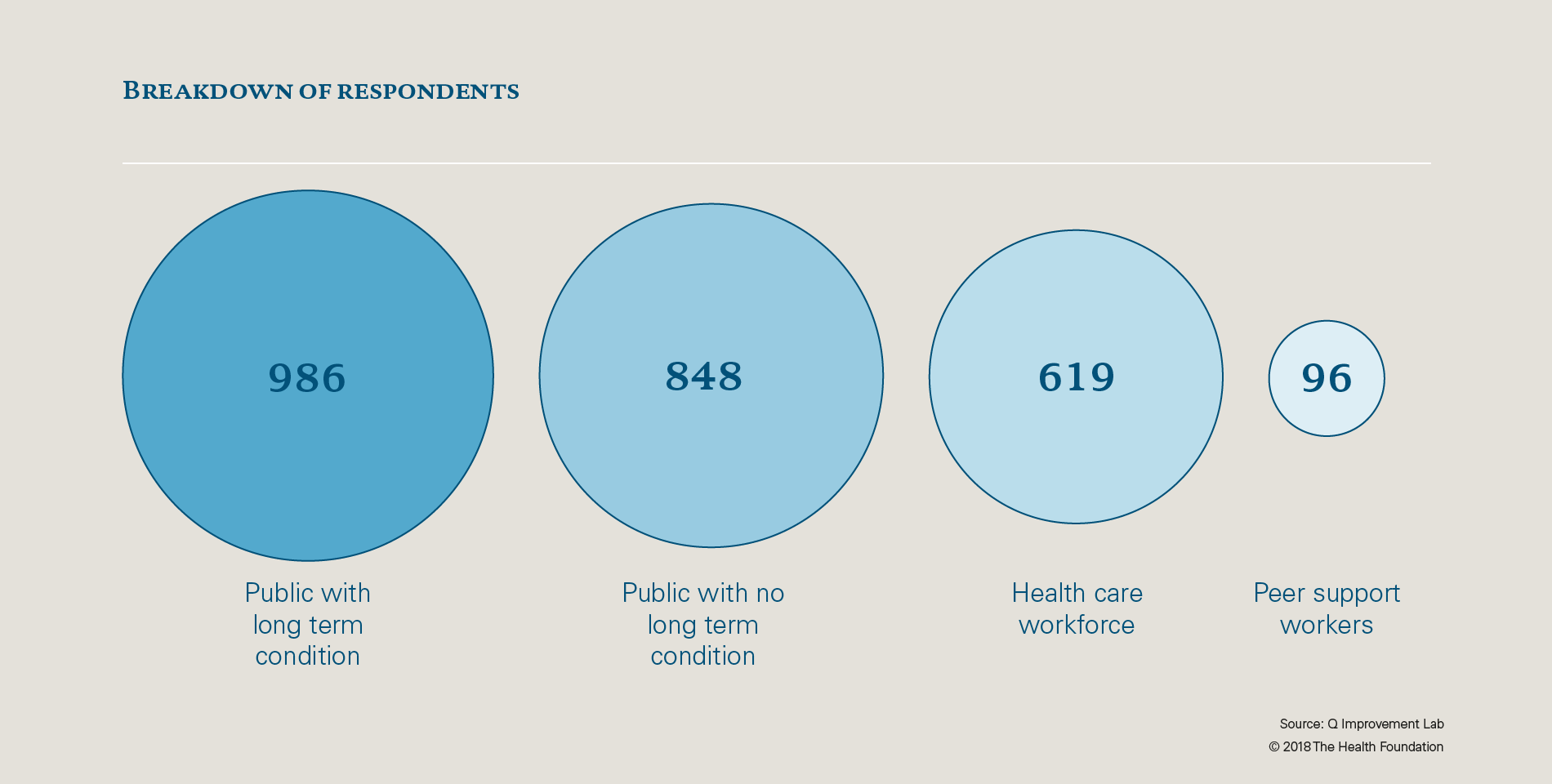

We conducted the survey in partnership with YouGov, and it was launched in December 2017. We collected 2,666 responses in five weeks. To our knowledge, this is the biggest peer support survey to be conducted in the UK.

All of the respondents were over the age of 16 and demographically representative of the UK population.2 The sample of the public was weighted towards those who identified as having a long-term condition – this is because we were particularly interested in their viewpoints as they are a population the evidence suggests might benefit most from increased awareness of and access to peer support services.3

The chart below shows the breakdown of respondents.

What we found

Interactions with peer support

Conducting a peer support survey like this at scale has allowed us to learn more about people’s interactions with and utilisation of peer support at a national level.

Use of peer support by the public

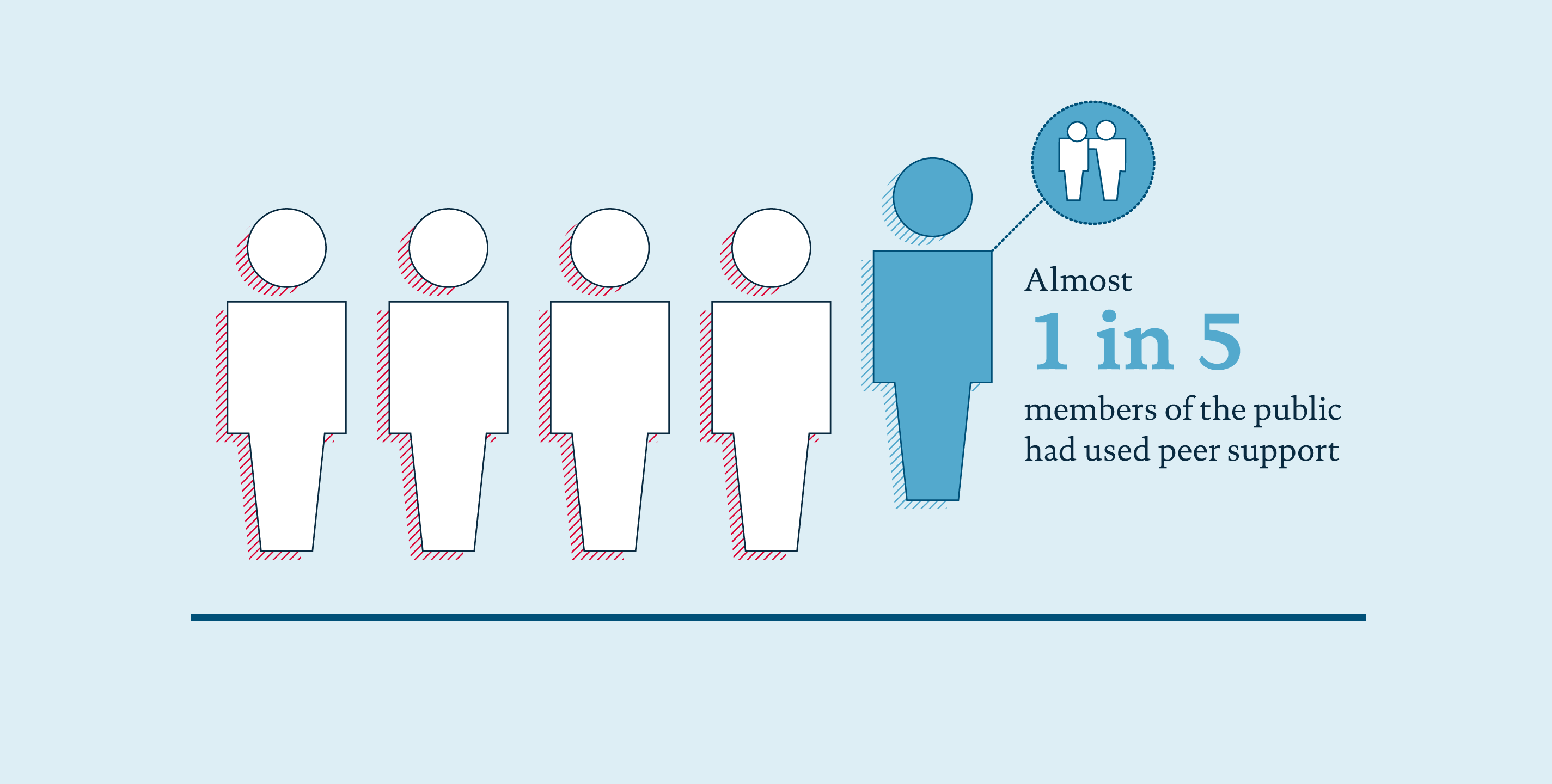

- Almost one in five members of the public had used peer support.

- Those with long-term conditions were more than twice as likely to have used peer support as those without a long-term condition.

- Three women had used peer support for every two men.

- Those under 65 years of age were almost twice as likely to have used peer support as those over 65.

Referral to peer support by health care professionals

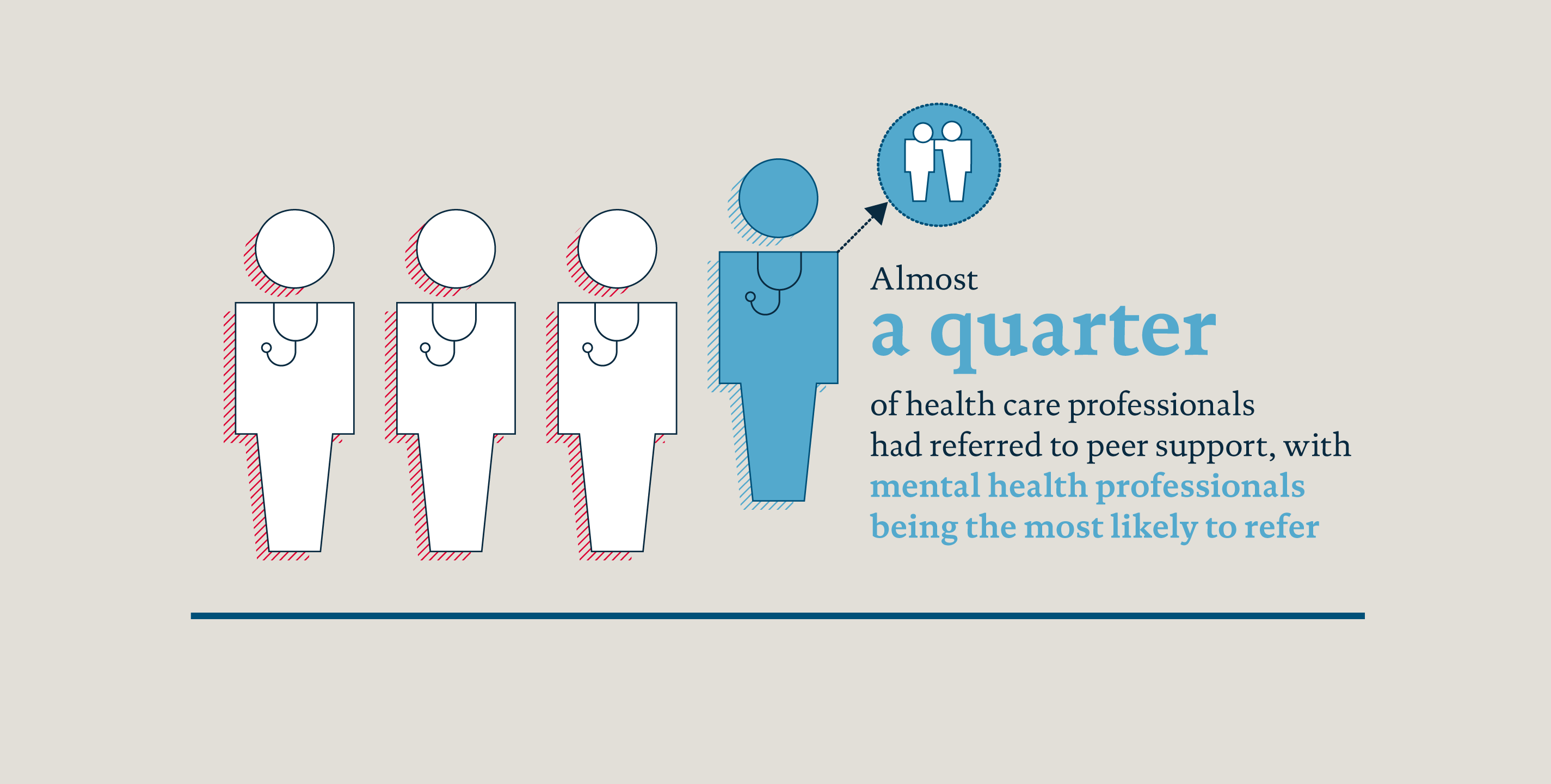

- Almost a quarter of health care professionals had referred to peer support.

- Mental health professionals were most likely to refer to peer support, with just over half saying that they had referred.

- 39% of GPs, 38% of hospital doctors and 35% of nurses and midwives said they had referred to peer support.

What did the different groups prioritise?

We were particularly interested in understanding whether different factors were important for the health care workforce, peer support workforce and the public. We also wanted to find out if people who had used peer support valued different things to those who had not, and whether having a long-term condition influenced what people thought was important.

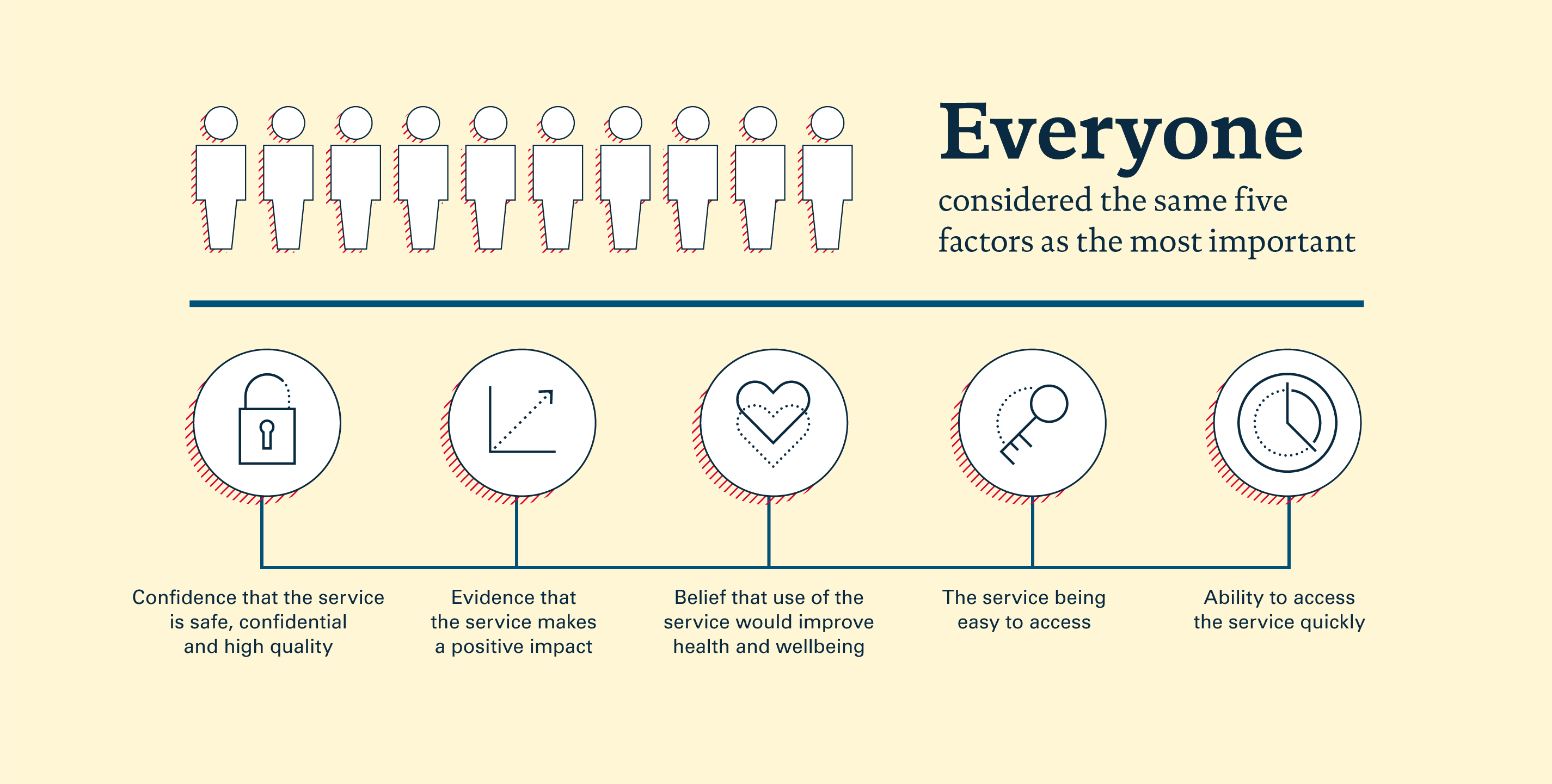

Using individual respondents’ priorities, a mathematical algorithm calculated the overall priorities for each of the three groups (health care workforce, peer support workforce and the general public).4 Our analysis showed that the health care workforce, peer support workforce and the public who hadn’t used peer support all considered the same five factors as the most important, although in slightly different orders. These five factors were:

- Confidence that the service is safe, confidential and high quality.

- Evidence that the service makes a positive impact.

- Belief that it would improve health and well being.

- The service being easy to access.

- Ability to access the service quickly.

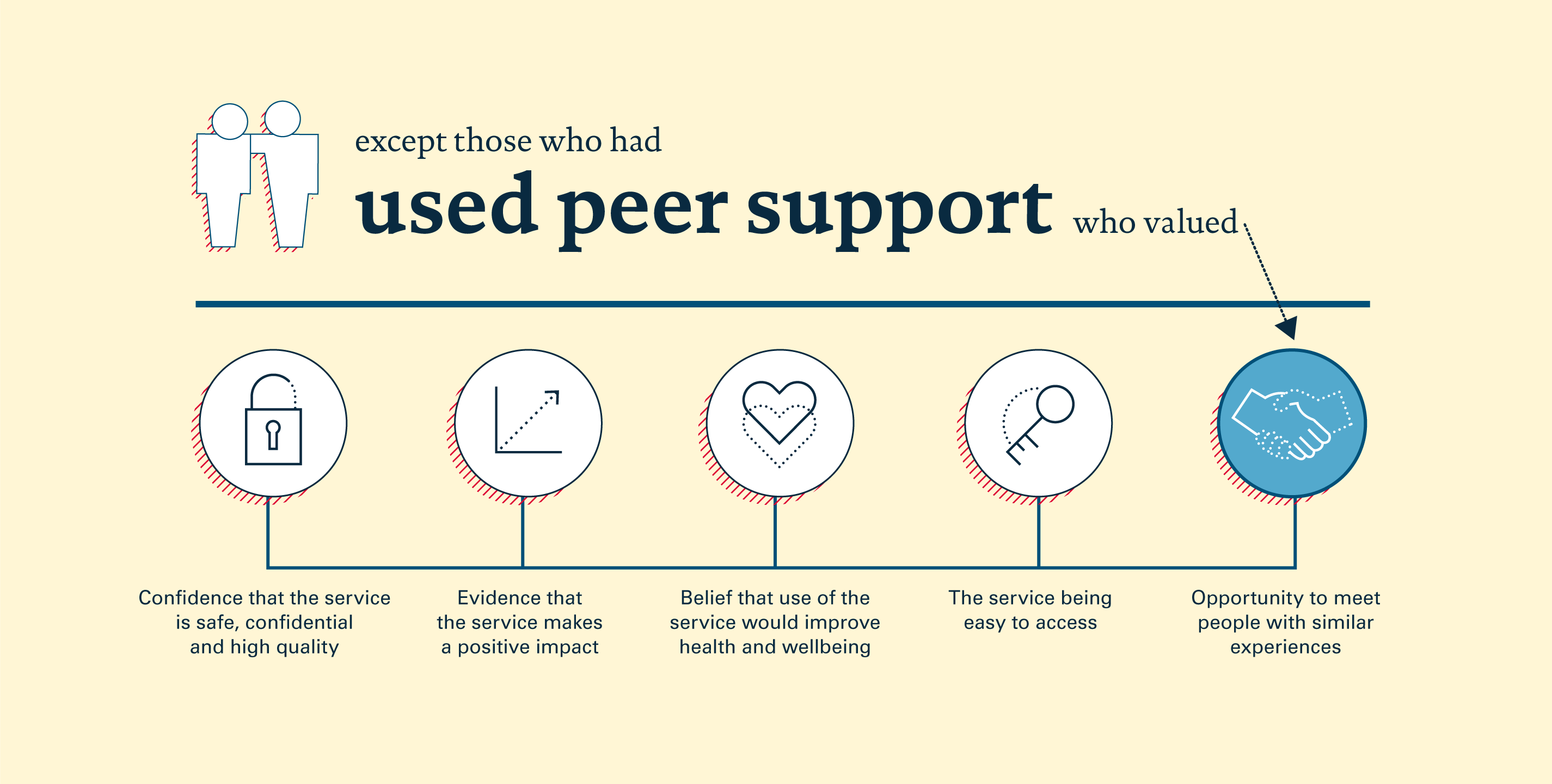

When it came to those members of the public who had used peer support, our analysis found that an opportunity to meet people with similar experiences was now considered to be one of the top five most important factors. But the other five factors above all made it into the top six for this group.

The health care workforce considered evidence that the service makes a positive impact more important, whereas the public who hadn’t used peer support and the peer support workforce both considered belief that it would improve health and well being as a more important factor.

The public who had not previously accessed peer support placed more value on the service being endorsed by a health care professional than the health care or peer support workforce.

Those working in peer support felt that an opportunity to meet people with similar experiences and stories from people who have benefitted from the service were more important than members of the public or health care workforce did.

Members of the public who had used peer support think that the service being endorsed by a health care professional is less important than those who have not previously accessed it.

Across all sub-groups we analysed, the service being easy to access was considered more important than the ability to access the service quickly.

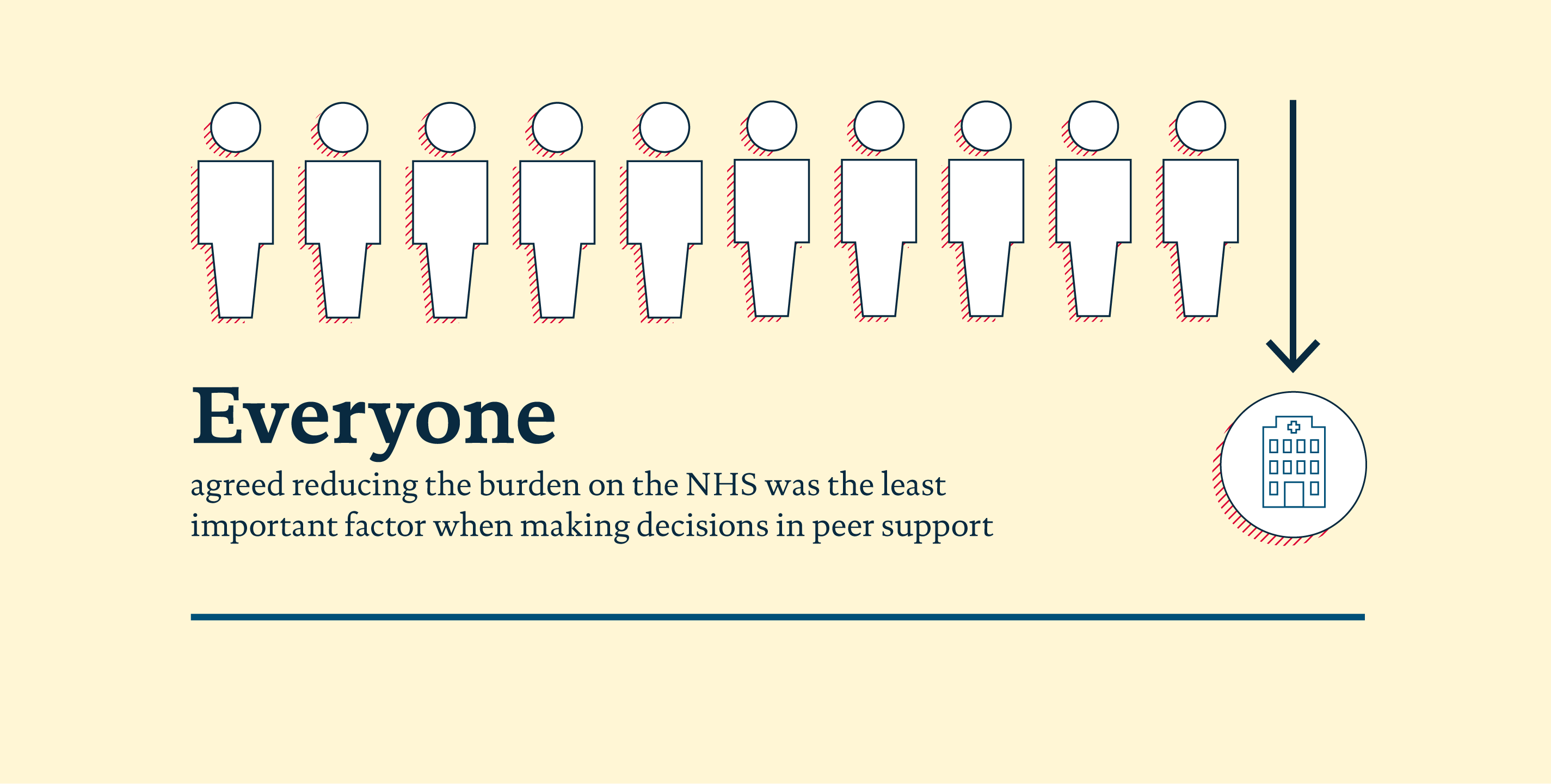

Reducing burden on the NHS was uniformly ranked across all of the subgroups as the least important factor when making decisions around peer support.

In addition to all of the above, our analysis did not identify a statistically significant effect of sex, location, age or ethnic background on what any group considered important when making a specific decision.

How these priorities interact

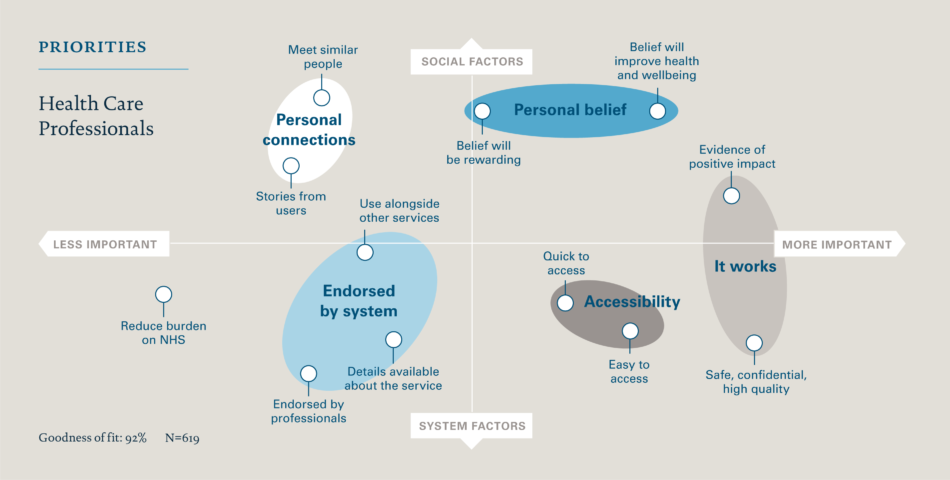

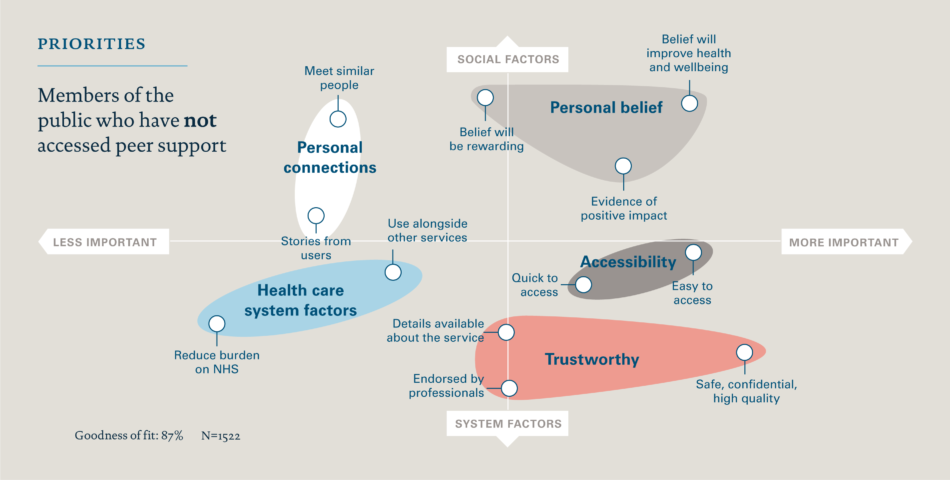

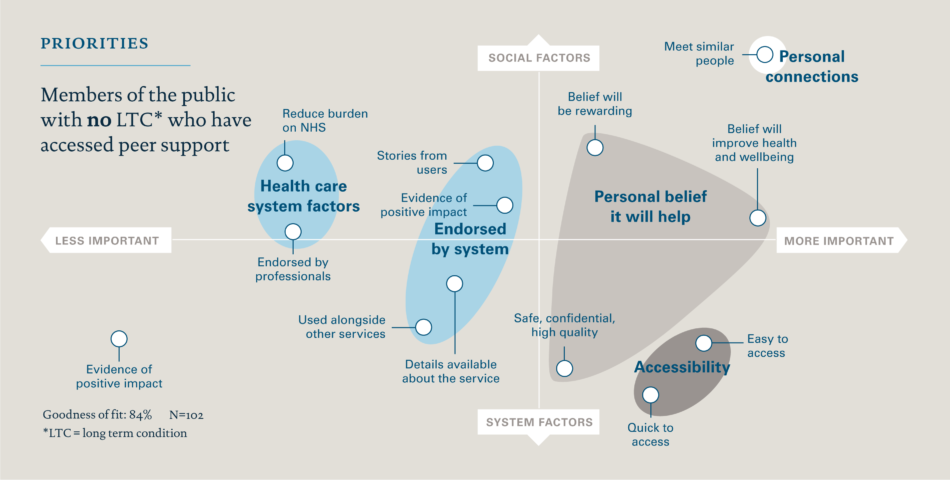

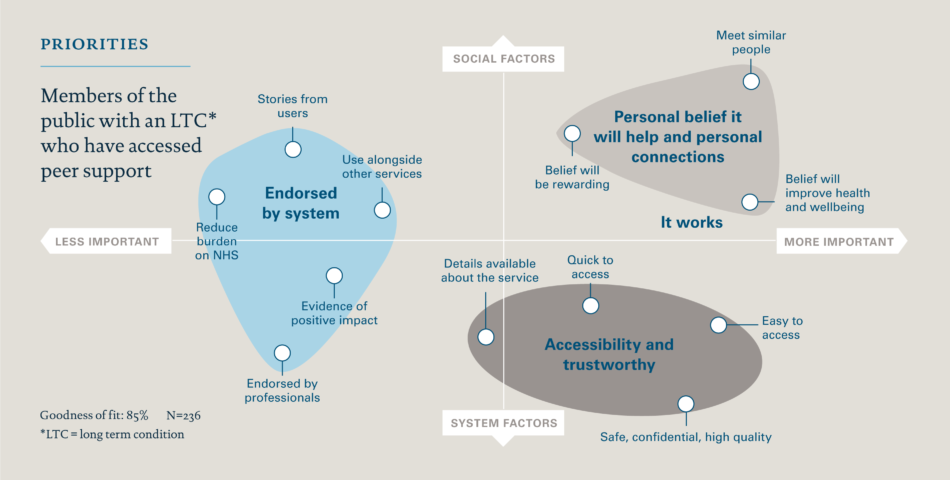

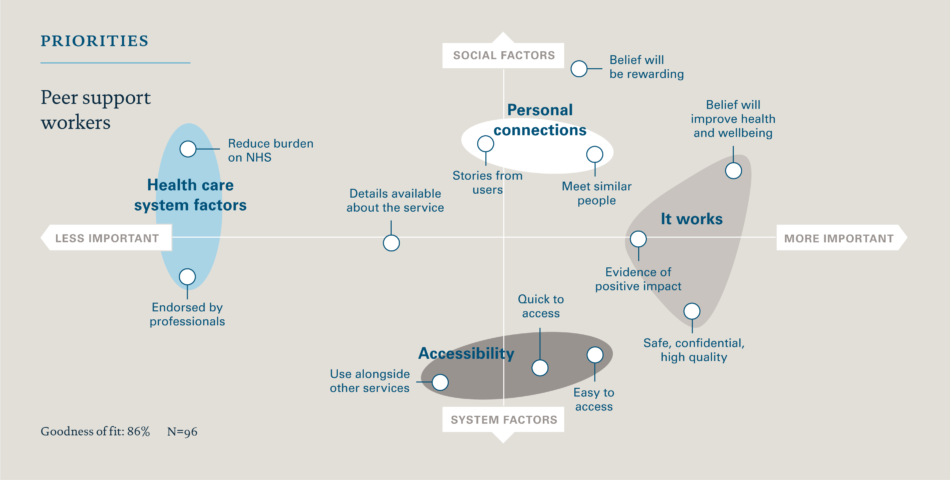

We carried out further analysis to give additional insight into the group rankings. We adapted a technique common in psychometric research to visualise the group preferences in a 2D “importance map” of the options and how they cluster together.

The clusters show factors that tend to be ranked similarly by people so that a single cluster of factors might represent a broader “priority” that contains each of the factors within that cluster. For instance, the cluster of “easy access” and “quick access” represents a broader priority of simply “good access”.

The importance maps show that there were some factors which clustered together in a similar way for the different sub-groups. Clusters of factors linked to personal connections, accessibility and health care system factors (such as reducing the burden on the NHS and ability to use alongside other services) came up multiple times.

For the health care workforce, three broad factors are important for referring to support: that it objectively works, that they believe that it will help and that it’s accessible. There were no differences for those who had referred to peer support compared to those who hadn’t. As the same things were important to those who had and had not referred, we might infer that unless all three factors are met, health care professionals will be less likely to refer people to peer support services.

For members of the public who had not accessed peer support, three slightly different factors were important: belief that it will help, trustworthiness and accessibility. However, for those with no long-term condition who had previously accessed peer support, although accessibility and belief it will help were important, the opportunity to meet people with similar experiences was also considered to be extremely important. It would be interesting to explore whether this relates to the preferences of people who have accessed peer support, or the value people have gained from meeting people when they have experienced peer support.

Translating the peer support survey insights into impact

This research has given us new insights, not only in terms of what people find important when making decisions around peer support but also about usage and referral rates. We think there are opportunities to use this new learning and apply it in practice to support the uptake of peer support services by those who could benefit from it.

During March and April 2018 we spent time working with Lab participants and other key stakeholders to think about how the findings could be used in practice.

The ideas, although wide ranging, could be collated into the following recommendations:

- Use insights to tailor peer support services – People working in peer support services could use these findings to communicate or design services in a way that specifically meets the needs of the target audience. For example, emphasising access and trustworthiness to members of the public.

- Use insights to raise awareness about peer support – As outlined in the Learning and insights on peer support essay, there are challenges around effectively evidencing the benefits of peer support. This survey generated some new findings which could add to the existing evidence base around peer support in terms of how much it is used and referred to. For example, uptake of peer support by the public might increase if people were aware that as many as one in five people have used it to help manage their health needs as people tend to place more value on something if they know other people do too. The findings can also demonstrate the value which people place on peer support by highlighting the factors which matter the most to people who have used it, for example: belief that it would improve health and well being and an opportunity to meet people with similar experiences.

- Use insights to engage health care professionals – Although the routes to accessing peer support are varied, referral to peer support from a health care worker has been of interest during the Lab process. Our findings show what is valued by the health care workforce. Therefore, when trying to get buy-in from them, it would be useful to cover content linked to the factors which they place more value on, such as evidence that the service makes a positive impact. In addition, findings from this survey could be used more broadly to demonstrate to health care professionals, and others, the extent to which peer support is valued and used by the public.

- Use insights to do more research – This research stimulated a lot of discussion around what other research could be done, not only in terms of decision-making in peer support but in peer support more widely. This piece of work focused on what people valued but not why they value it; further work could be done to try to learn more about that and the behaviours which go alongside it. It could also be good to bring some of these findings to life through stories and interviews to create a fuller picture of the peer support landscape.

Some specific questions that might trigger further research are:

- Are there differences in what people value, depending on what type of long-term condition they have?

- Now we know more about what people value, can we measure the extent to which these 12 factors meet their expectations?

- Are there differences in what is important to people when using peer support, depending on their route of access?

- What are some of the differences in using peer support for men and women, and older and younger members of the population?

In addition to the recommendations outlined above, there needs to be energy and effort committed to spreading the findings from this research. The Lab community proposed several different and creative ways to share the findings such as animations, podcasts and posters. These could allow the key insights to be communicated in an engaging way and could provoke further conversation and reflection. Responding to some of these suggestions, the Lab has created infographics and key images for sharing via social media and other communication materials.

Lab participants suggested a range of organisations, charities and networks from around the UK to share these findings with. We will be working with our Lab community to spread and share what we have found over the next few months.

These new insights into peer support have allowed us to bring people together and stimulate conversations about how they could be used in practice to: communicate more effectively, increase buy-in and understanding, and contribute to improving access to peer support overall. This research only begins to scratch the surface of what could be learned about opinions and behaviours in peer support and we hope it provides a springboard for further work.

Limitations to the peer support survey

As with any piece of research, there are limitations to the work we undertook. We tried to collect a large enough number of responses from which to draw population level conclusions. In addition, we ensured that there were a sufficient number of responses from different national and black and minority ethnic (BME) groups to ensure the sample was representative of the wider UK population. However, a sample can never truly represent the viewpoints of all those in a population and some of the conclusions we draw may not be applicable to all.

Prior to launching the peer support survey we also carried out rigorous testing to ensure that the survey used easily accessible language, was succinct and easy to take part in. We included an explanation of what peer support is, to help people understand the questions better, and provided a link to a video which described and exemplified peer support. Despite those efforts, there is a chance that respondents to the survey misunderstood what is meant by peer support and what was being asked of them in the survey.

The survey was delivered in English and designed to be completed online via a computer, tablet or mobile device. Therefore, this study is limited to fluent or proficient English speakers who were able to take part electronically and does not represent the viewpoints of those who were unable to take part due to the language or platform that were selected.

The survey was intentionally short so that it was easy to complete and to allow respondents to focus on the main element of our research, the ranking exercise. As a result, there were many questions that would have been interesting to ask that were not included in the peer support survey. We hope that although this might be seen as a limitation, this could encourage people to take the research further by asking additional questions.

For any questions about the research methods or analysis, please contact the Lab team.

Next steps

- If you work in peer support, consider how you tailor your messaging to communicate the elements which are considered most important to the potential users.

- If you are interested in researching peer support, think about how these insights might be used as a springboard to explore behaviours in peer support more deeply.

- Share these findings with your colleagues and networks who might find them interesting by tweeting one of our infographics or sharing the link to this essay.

- Use these new findings to prompt local conversations with the public and with health care professionals – your community may, for instance, rank different factors as being more important – which you can explore and respond to.