- Project one

- #5

- August 2018

Learning from the Lab’s approach to evaluation

Learning and insights from evaluation in the pilot year

Evaluation is key to the Q Improvement Lab (Q Lab); as a new initiative launched in 2017, it was important to take the time to learn from what was going well, seek feedback and reflect on what could be improved. We were fortunate to have had the resources, finances and time to commit to evaluating the Lab. This investment yielded invaluable insights, allowing us to understand how and in what ways the Lab is best place to support change. The purpose of this essay is to share our learning and insights on how the Q Lab has approached evaluation, as well as tools that we have found helpful which others working in health and care may wish to draw on.

We know from the fields of psychology and other social sciences that as human beings we have a tendency to believe what we want to believe. We have a tendency to see things in positive ways because we have high hopes that what we are doing is good. But we also have the capacity to convince ourselves that good things are happening when, in fact, they are not. ‘The mental mind-set for evaluation is the willingness to face reality. The mechanisms, procedures, and methods of evaluation are aimed at helping us test reality.’1

Yet the road to ‘testing the reality’ of the work you are doing can be a challenging one. Evidence and experience tells us that tensions can arise between evaluators, those they are evaluating and other stakeholders due to issues including a lack of shared understanding of the goal, data burden, confusion about roles and the discomforts of being studied.2

We have taken several practical steps during the Lab’s pilot project to try and mitigate some of these difficulties, ranging from having early conversations with our independent evaluation team, RAND Europe, about expectations and data collection, through to generating tools and approaches to help us capture some of the tacit knowledge the team has developed along the way. Developing a culture of learning3 has been perhaps the most important step we have taken; to be open to receiving feedback, seeing the reality of what is happening and making decisions about changes or adaptions we may need to make.

There is much more we can do to continue to develop this learning culture and to develop sophisticated ways to measure and evaluate success and we hope this essay will prompt others to share insights and experiences they have in this field. We’ve attempted to tell the story of the Q Lab’s evaluation and draw out particular insights and examples that may be of wider interest to those working within improvement or innovation, as we continue to learn.

What did we evaluate?

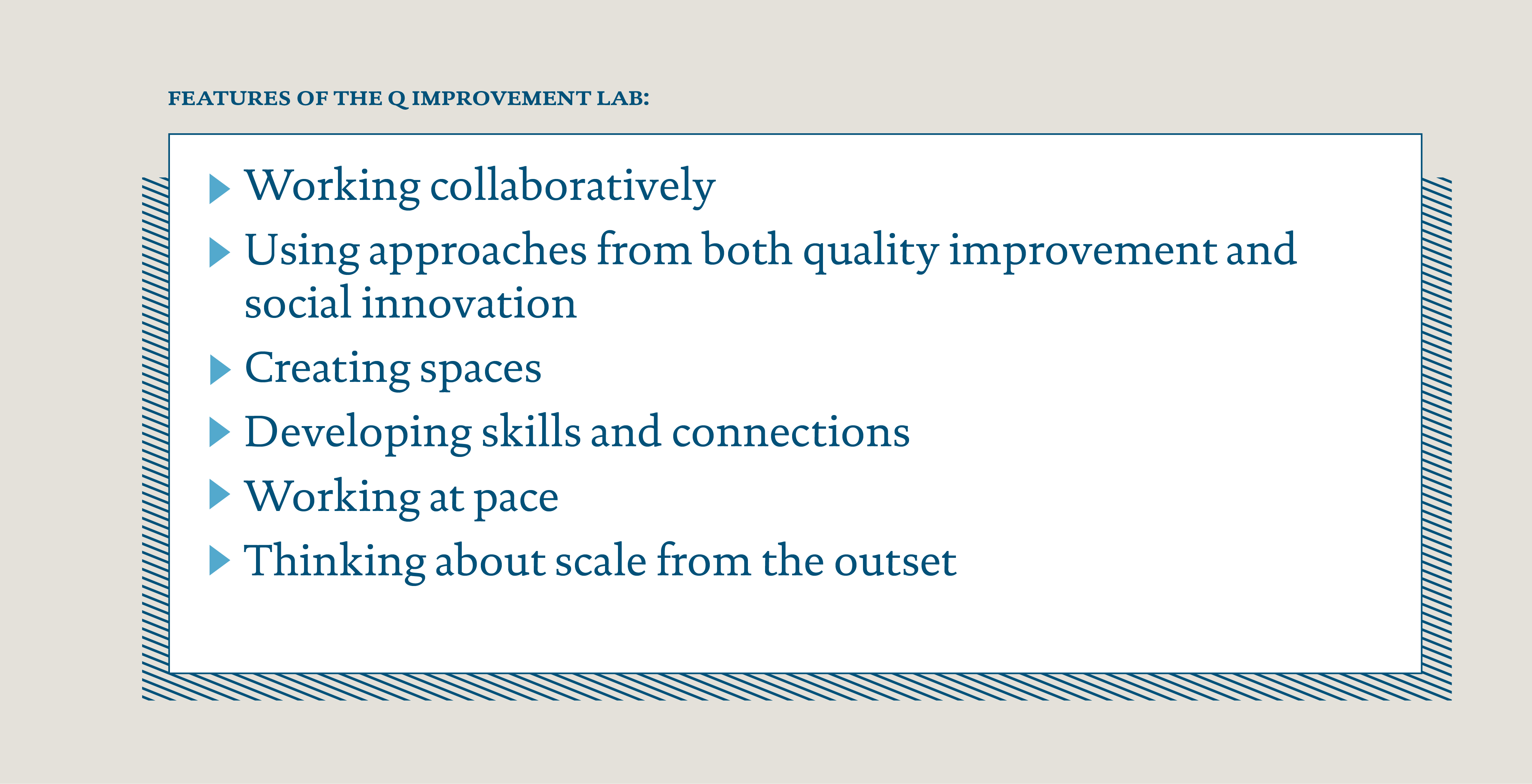

The Q Lab is an initiative led by the Health Foundation and supported by NHS Improvement, offering a bold new approach to making progress on health and care challenges.

Working on a single topic for 12 months, the Q Lab brings together organisations and individuals from across the UK to pool what is known about a topic, uncover new insights and develop and test ideas that will improve health and care. For more background information about what the Q Lab is, take a look at the What is the Q Improvement Lab? essay.

The Lab seeks to achieve four main outcomes:

- Build a rounded understanding of the issue

- Generate and test ideas for improvement

- Develop skills for action

- Disseminate learning widely

For more detail on what the Lab hopes to achieve and how we seek to achieve it take a look at Impact that counts essay.

The pilot project explored what it would take for peer support to be more widely available. In addition to making progress on peer support (for more information see the Learning and insights on peer support essay), the aim of the 12-month project was to also learn about whether the Lab approach is adding something valuable to the busy world of health and care improvement. To do this, there were two strands of evaluative work:

- Team-led internal learning and reflection processes

- Independent external evaluation led by RAND Europe

The Lab’s first project was a pilot, everything we did was done for the first time and so evaluation has been essential to iterating and improving the Lab model.

Internal learning and evaluation

People need time and safe spaces to reflect on how their work is contributing to the aims of a project, the impact it is having, and what is and is not working. They also need support to articulate these reflections, as well as team commitment to act on those reflections and make changes.

Over the last 12 months, the Lab team has developed internal evaluation processes to capture the its learning and impact; purposeful tools and actions that surface and record our learning to see how and where we are making progress on our project outcomes. Here we outline some of the methods used by the team and what we learned from using them.

Learning log

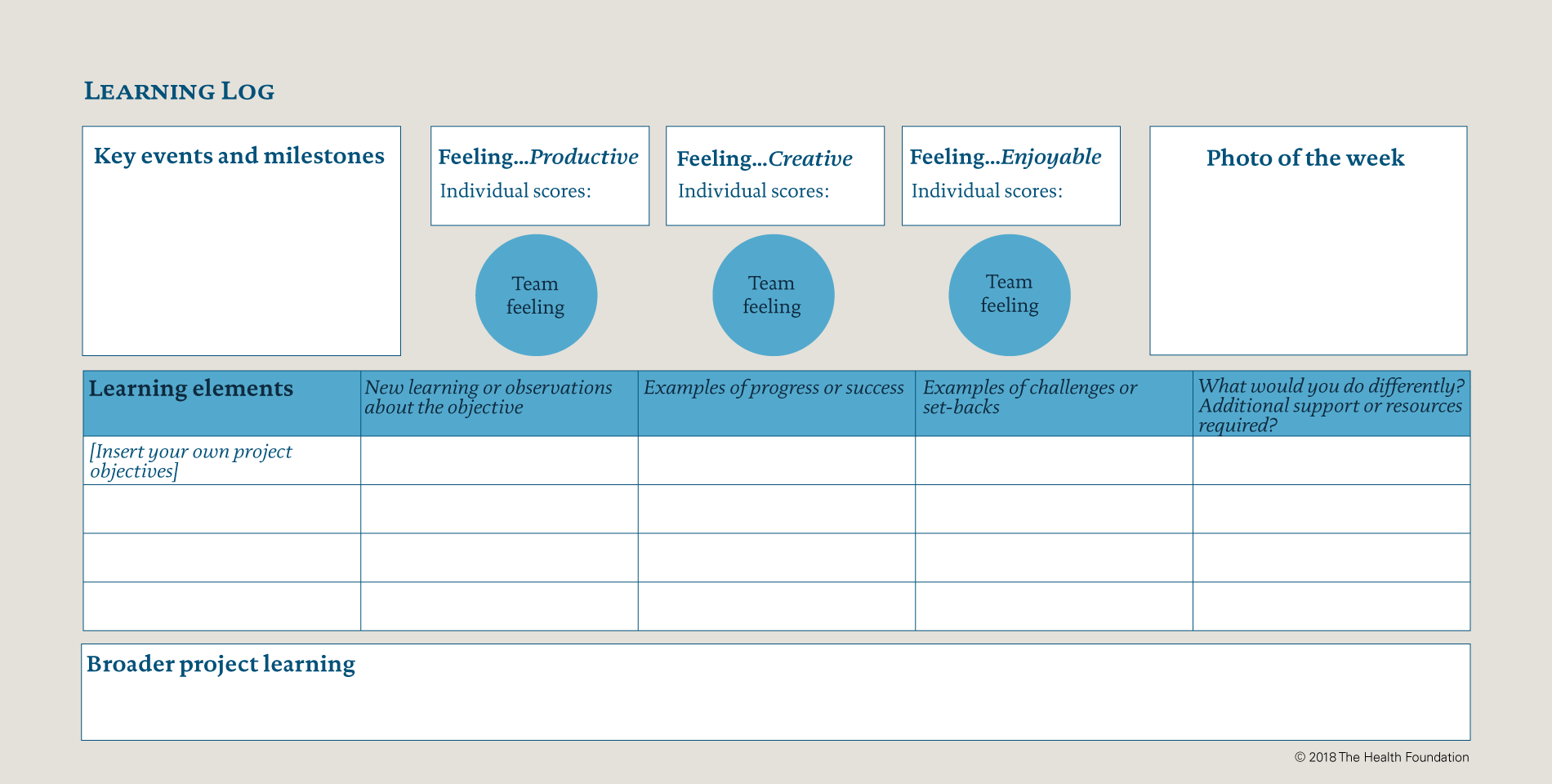

To capture the learning during the project, we developed the learning log.

This weekly diary helped the team document what we were doing and what impact we had seen and how we felt during the project and capture learning that doesn’t lend itself to metrics and can be hard to verbalise, alongside some clear learning outcomes and data. For example, throughout the Lab process, the team was building new relationships and gaining new perspectives on the topic and the Lab approach. The learning log provided a good place to record some of that learning which may not have been captured in a specific output or by the independent evaluators. It was just as important to capture insight about what wasn’t going well, or where we didn’t feel we were making as much progress as hoped, as it was to identify positive impact.

The log was designed to be linked, in part, to elements that were covered by the external evaluation so that we could consolidate and compare what was captured by the Lab team and the evaluation team. However, other elements of the learning log were in place to gather insights that were at risk of slipping through the net, such as capacity concerns within the team and thoughts on how things could be done differently.

The format is user-friendly making it quick to complete on a week-by-week basis and, by providing a combination of structured and open questions, the log is able to collect a breadth of learning. Small touches like having a picture of the week helped to ensure that completing and reviewing the log had an element of fun to it. We feel this tool could be readily used or adapted for other initiatives or organisations to monitor their learning over the course of a project.

The log allowed us to have structured conversations about how the team felt it was operating, identifying trends, and how to respond to risks and opportunities. We found the learning log a helpful way of making these conversations more likely to happen and richer in content.

After-action reviews

An after-action review (AAR) is a quick team debrief that proved very useful throughout the Lab process, and is a tool that the wider team working on Q – the growing community of people with experience and expertise in improving health and care – uses often. First used by the Army on combat missions, the AAR is a structured approach for reflecting on the work of a group and identifying strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement.4 This tool is useful in all contexts for people who want to maximize learning from their work. Regardless of project outcomes, there are always successes to document and lessons to learn.

An AAR provides an opportunity for the team to reflect together on something that has taken place, such as a meeting or a specific piece of work. At the Lab, we use a truncated version of the full AAR which focusses on ‘what went well’ and what would be ‘even better if’. This approach can be used after any meeting, event or activity – no matter how big or small – to capture the thoughts and reflections of the team.

The AARs were an important part of our learning during the first year as we carried out a number of activities, for example workshops, on a regular and repeated basis. Our priority was always to improve on the last one by considering what had worked well and what could have been better when planning the next. By conducting an AAR shortly after completing the activity, everyone’s opinions were still fresh in their minds and these reflections were key when scoping and planning other similar activities. The simplicity of the AAR as well as the balance of celebrating and trying to emulate success, and openness to discuss areas for improvement also ensures that the morale stays lifted and the feedback feels constructive.

During the meeting, I witnessed many other examples of team members raising doubts or concerns about what was being discussed and these were always well received. The team has a culture of openness and shows a learning attitude: divergent ideas are welcome, not discarded, even when they force the team to rethink, slow down progress, make new plans or abandon potentially promising avenues

RAND observation

Developing and Testing phase

Mapping our experiences

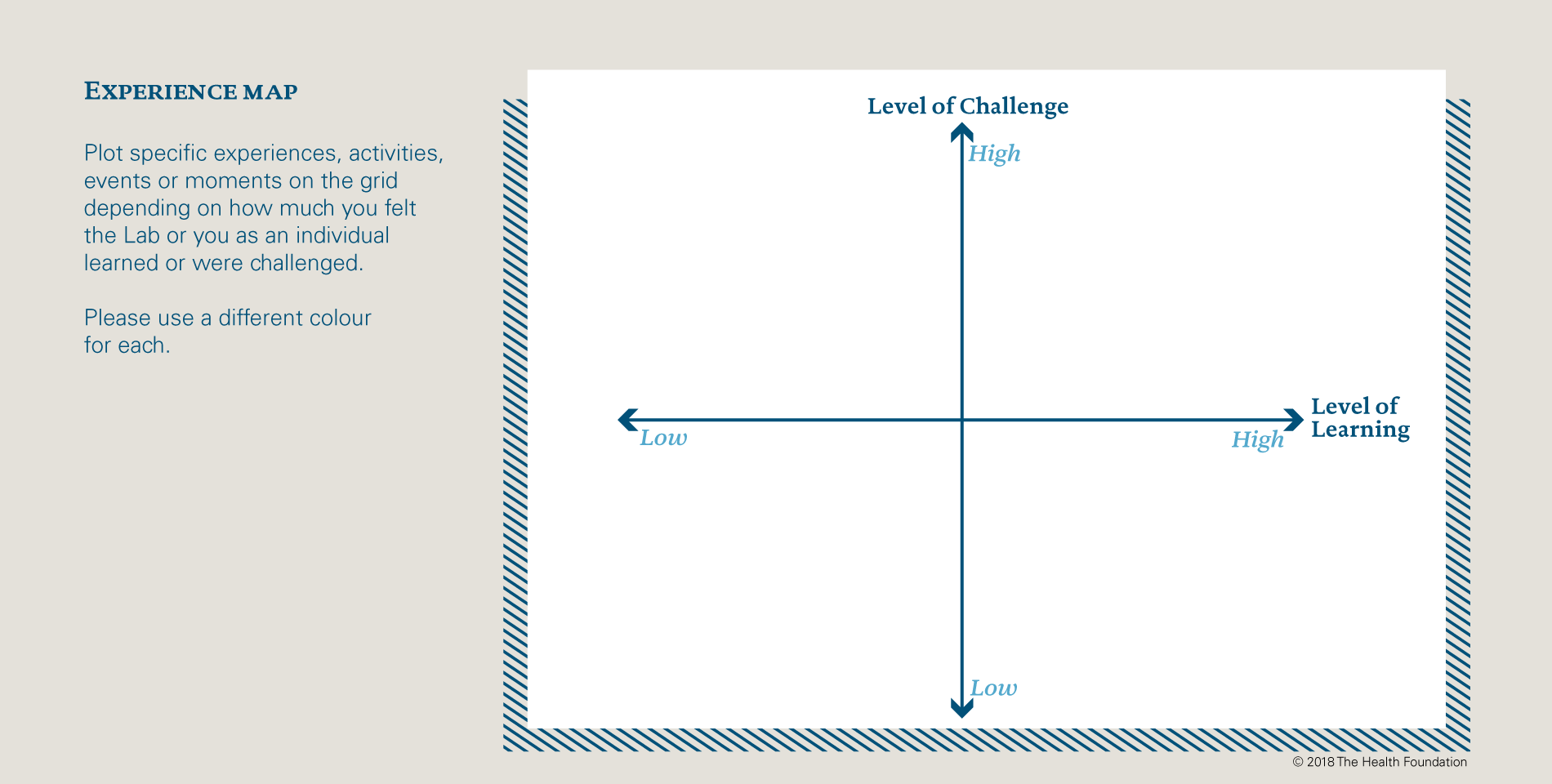

Another tool that the Lab developed and tested, that could be used as part of a more extensive AAR, was an experience map.

During this exercise, we mapped the activities that had been done, on a team or individual level, according to how challenging the task was to do, and the level of learning gained from doing that task. The map contained activities, events or milestones which were considered important by the person completing the mapping exercise and provided an opportunity to reflect on all that had been achieved in a set period of time.

This tool helped us understand which of the activities were the most worthwhile for the Lab – in terms of providing minimal difficulty and maximum learning opportunities – and which were labour intensive but didn’t bring about helpful new insights or learning.

The experience maps were completed by individuals and then discussed as a team. It was interesting to assess to what extent each of the experience maps correlated with each other. Although as a team we are working towards the same goals, different people will have different perspectives on what they find challenging and on what they are learning. This tool served as a good initiator for discussions around how different team members felt about different activities that the Lab was carrying out. Exercises such as this helped the team learn more about each other, align our ways of working and refocus the team before starting the next piece of work or working towards the next project milestone.

Independent evaluation of the Q Lab

Our intention was always that an independent evaluation would play two roles in the Lab’s first project. Firstly, that the emerging findings inform and shape the development of the Lab throughout year one. Secondly, to provide us with rich data and insights to help us make decisions about how – and if – the Lab approach should be developed going forward.

RAND Europe led a series of evaluation activities using a combination of traditional methods including semi-structured interviews, surveys, focus groups and desk-based research. In addition, ethnographic techniques and an engagement survey helped RAND to capture more nuanced insights about the Lab approach.

Insights were collected through activities which involved key Lab stakeholders: the Lab team, colleagues at the Health Foundation and Lab participants (a 200-strong group of people and organisations from across health and care who volunteered to be contribute skills, expertise and time to working with the Lab).

Evaluation activities were designed around the three phases of the Lab:

- Research and discovery: Investing time upfront, drawing on the best evidence and bringing new voices and perspectives to bear, to dig deep and understand the root causes of the challenge.

- Developing and testing ideas: Using the findings from the ‘research and discovery’ phase to pinpoint key opportunities for impact and create momentum for change. This may involve developing a new idea and testing it with Lab participants, or through other vehicles, such as Q Exchange. Alternatively, there may be an idea that is already in development where the Lab can help speed up the pace and move it on to be scoped, tested and adopted.

- Distilling and sharing learning: Collating what the Lab has learned and how the new insights can be practically applied. Learning is shared widely and people and organisations are supported to adapt and adopt insights and ideas.

By collecting data at key moments, we were able to engage Lab participants, often during Lab workshops, with evaluation activities.

Workshops can be intense, energising and tiring days. Lab participants were highly engaged during these workshops and therefore they were well placed to provide detailed feedback to the evaluators. There is, however, a risk associated with running evaluation activities at key events, such as workshops and kick-off meetings, as this is when people are most highly engaged, but also perhaps when they are tired after a busy day. Therefore, the findings might not be truly reflective of the project as a whole.

Ethnographic techniques were used to capture a fuller picture of the Lab approach and activities. Every month, the Lab team was joined by an ethnographer who observed and reflected on our ways of working. By being in the room, the ethnographer was exposed to conversations, meetings and day-to-day work which gave the evaluators a richer and more accurate idea of the work of the Lab and to witness first-hand the team tackling challenges, engaging with Lab participants, iterating our approaches and planning for key events.

Collaboration is a core element of how the Lab works, and we wanted to use the evaluation to assess how we collaborate, and how effective that collaboration was (see our Ways of working essay to be published in October 2018). An engagement survey was developed by RAND to help understand the nature and quality of the relationships generated through the Q Lab; it allowed us to explore the type of relationships generated within the Lab participant group, how these are being used and mobilised, and how they contribute to the Lab’s outcomes. The survey also offered an opportunity to explore the ‘routes to engagement’ (how people found out about the Lab and the ways in which they engaged with the work) and how these evolved during the Lab life cycle.

Although the evaluation with RAND had an agreed set of formal outputs such as a comprehensive report at the end of the project, we met with the evaluation team at five-weekly intervals so that they could feedback their thoughts. These meetings were a helpful opportunity for the team to pause and reflect, take in the feedback and consider how to use the learning in our ways of working. These feedback cycles contributed to the Lab’s ability to iterate and improve during the first year.

The final report from RAND’s evaluation of the Q Lab is available to read.

I really think that the feedback element is so well conducted, at regular intervals, and I think it’s really encouraged the feedback, whether that’s positive, negative or anything in between, really. And I really do feel like it is acted upon and taken seriously, which is nice. Again, it doesn’t just feel like you … they’re saying stuff and it disappears. […] Because it is an experimental process, it is developing and nobody is denying it’s not a work in progress. And I think that is very nice because you do feel like you can have your [stamp] on it.

Interview with Q Lab participant

Distilling and sharing learning

Integrating evaluation into the Lab approach

This essay captures some of the core elements of the Lab’s approach to evaluation during the pilot year. We found it to be important to enter what you might call a ‘psychological contract’ with the evaluation and learning approach and integrate this into our ways of operating.

There are however a number of judgements to be made when planning evaluation, and we are still working through these and making decisions about how to get the right balance between reflection, learning, listening and delivery. Some of the questions we are actively discussing as we move into our second year include:

- When should you act quickly to respond to feedback, and when should you resiliently focus on goals and not change course at the first signs of any issue?

- When are teams most well placed to review a major milestone? How do you balance generating reflections when an activity is fresh in people’s minds, versus having enough distance to be objective about successes and failures?

- What is the role of personal, professional feedback, alongside wider team or initiative feedback? How can you safely test individuals preferences for this?

- How much is too much reflection? When does your work need you to drive forward and be in ‘action’ mode, and when does your work require you to slow down your thinking and take stock?

Finding ways to have these conversations with teams and stakeholders, choosing the best moments to do so, and recognising that there are seldom ‘right’ answers to them has not been easy but has been highly valuable, and these prompt questions may be of use to other teams wanting to work through how to embed evaluation and learning.